The legend says a meal sat untouched on the table and a chair lay knocked over. Relief keeper Joseph Moore found something else when he pushed through the door on 26 December 1900. The kitchen was cleaned down, pots washed and stowed, everything in order. That gap between the legendary scene of chaos everyone ‘knows’ and what the first witness actually recorded drives this investigation. We’re tracking how administrative paperwork from 1900-1901 got buried under a century of fiction.

This is one part of a multi-part case file. Return to the main Flannan Isles Legacy investigation to see all related articles.

Definitions in Brief

- Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB): the public authority that owned and operated Scottish lighthouses. In 1900, it set rules, employed keepers, ran relief ships, and investigated accidents.

- Relief tender: the small ship that carried stores, coal, and a rotating keeper to and from remote stations. Hesperus held that role here.

- Geo: a narrow inlet or gully in a sea cliff carved by waves. Geos can funnel water upward with force, making adjacent ledges dangerous in storms.

- Rogue wave: an unusually high wave that seems to appear out of nowhere, well above the average sea state. Not magic, just rare and dangerous. On a cliff it can run up far above the offshore wave height.

- Oilskins and sea boots: waterproof coat and trousers, and heavy boots, worn to work in spray and rain. In winter, no one goes out on Atlantic rock without them unless in a rush.

- Hundredweight (cwt): an old British measure of weight. Twenty hundredweight is roughly one imperial ton, a useful way to picture the mass of a dislodged rock.

Arrival at an Empty Rock

On Wednesday, 26 December 1900, the relief tender Hesperus reached Eilean Mòr, the largest of the Flannan Isles, after heavy weather had delayed the run for nearly a week.

Standard signals brought nothing back. No flag flew over the station, no keeper stood at the landing to greet the ship. Captain James Harvie blew the whistle, then fired a signal rocket. Still no movement ashore. He sent the relief keeper, Joseph Moore, across alone in a boat.

Moore climbed the steps, passed through the entrance gate, and reached the lighthouse. He found the outside doors closed, not locked. Inside, no sign of anyone. The clocks had stopped. The beds were unmade, as if the men had risen and started a normal day. The fire in the kitchen grate was cold and un-raked. In keeper routine, that means nobody had touched it for days. Moore checked the lamp room and the store. The island was silent.

Harvie sent an urgent telegram to the Northern Lighthouse Board that afternoon describing a ‘dreadful accident’. Worth noting what he didn’t say. Harvie wasn’t sniffing a crime or hinting at something supernatural. This experienced seaman read the scene as a weather tragedy from the start.

Procedural anomalies that triggered the alarm

- The light had been out for at least one night. The steamer SS Archtor recorded no light as she passed at midnight on Saturday, 15 December.

- No flag flew and no keeper met the tender. Both were standard practice.

- The station was closed up but not secured; gates and doors were shut, not locked.

These details set the clock. Something happened between Saturday morning, when the keepers completed their recorded tasks, and Saturday night, when the Archtor failed to see the light.

Inside the Lighthouse – A Scene of Order, Not Chaos

The interior evidence contradicts the chaotic scene that later took hold.

There was no half-eaten meal. No knocked-over chair. Moore and, later, Superintendent Robert Muirhead both describe a tidy station. The kitchen had been cleaned after the last meal.

Moore’s own report stated, ‘The kitchen utensils were all very clean, which is a sign that it must be after dinner some time they left’. The lamp had been serviced. The log, kept day by day in a bound book and on a slate for quick entries during the current shift, ran to 9 a.m. on Saturday, 15 December. No frantic notes. No prayers or tears on the page.

Here’s where the story gets unclear. The original documents point to an ordinary morning that ended with an extraordinary sea. The myths point to terror indoors. The evidence says one thing, the legend another.

Two details inside do matter for the reconstruction:

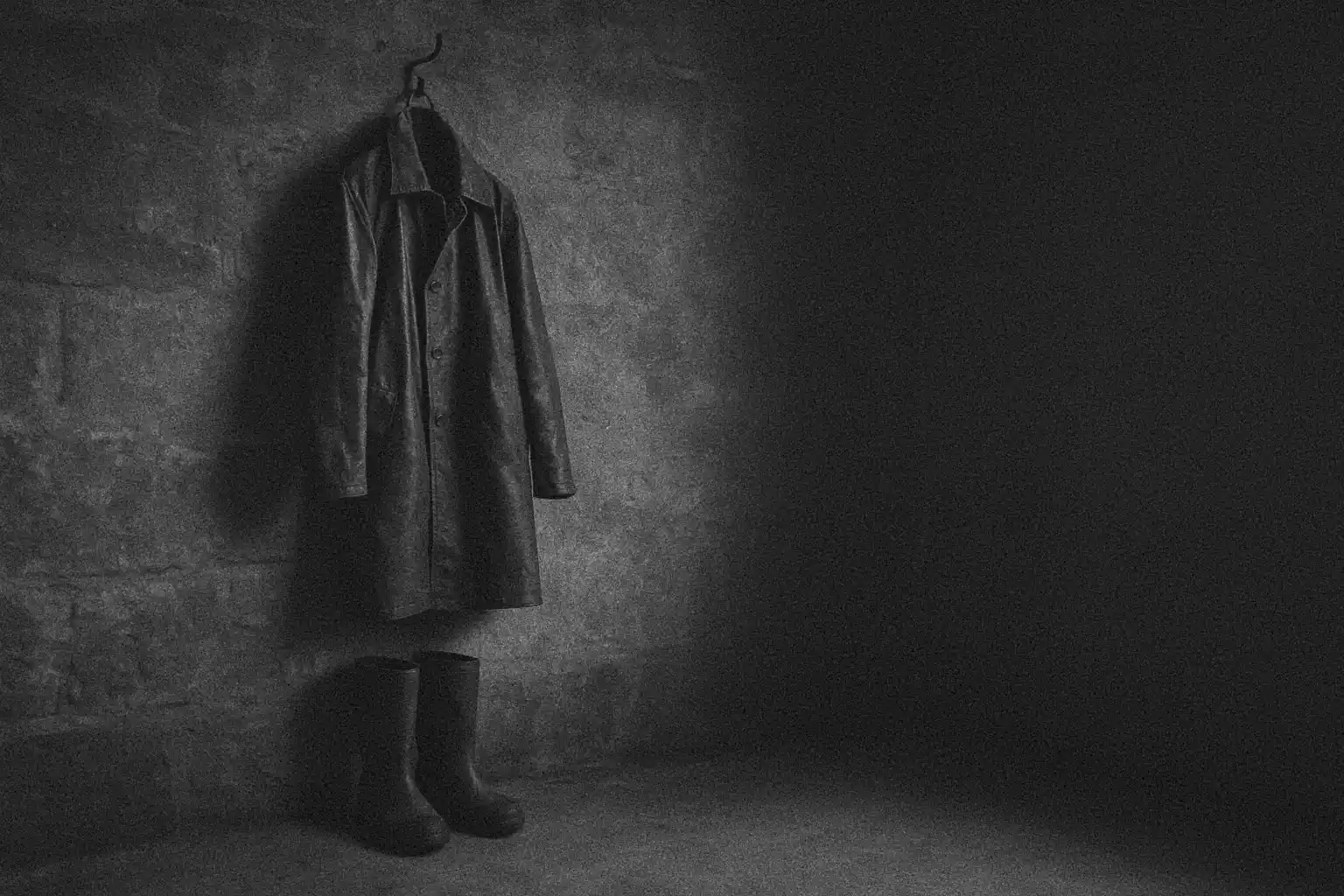

- Two sets of sea boots and oilskins were missing from their pegs. One set of oilskins remained hanging in the hall.

- The wall clock and other clocks were stopped. Keepers wound them as part of routine. A stopped clock suggests a week or so without winding, which fits the calendar gap to 26 December.

If two men were dressed for heavy weather and the third wasn’t, the most natural reading? The third left in haste. We’ll come back to that coat.

Myth vs. Record

| The Legend | The Record |

|---|---|

| A meal of meat and cheese sat uneaten on the table, a sign of sudden interruption. | The kitchen was found clean and tidy. Moore reported that 'the kitchen utensils were all very clean', indicating the men left after their meal. |

| An overturned chair suggested a panicked flight from the room. | No contemporaneous report mentions an overturned chair. The lighthouse interior was found in proper order. |

| Keepers wrote terrified log entries about a supernatural storm and one man crying. | The final log entries were routine weather readings. The terrified entries were a fabrication from a 1929 magazine story. |

The legendary details originate in a 1912 poem and were never recorded by the 1900 investigators.

The West Landing – Damage at Impossible Heights

The west landing sits below a cliff and runs into a geo. When a wave drives up that gully, it can explode upward. The relief party found damage that’s hard to explain without water reaching well above normal heights.

What the NLB investigation logged:

- A heavy store box, located more than 110 feet above sea level, had been smashed open, and its contents scattered.

- Iron railings at the landing were bent and twisted.

- A rock weighing around 20 cwt (roughly a ton) had been dislodged and moved.

- Turf at the top of the cliff, over 200 feet above the sea, had been ripped away. Solid water, not just spray, had reached that level.

For context, 110 feet is taller than a ten-storey building. If sea force tore open that box, the event was extreme. The landing had taken a beating. Something was loose or breaking free. That gives the keepers a reason to be there in foul weather.

The Board called it an ‘extra large sea‘ – their phrase for what we’d now call a rogue wave. Mariners had long described them, though scientific acceptance came much later. The Flannan evidence fits that modern understanding.

The Occasional Keeper, Donald McArthur, went out in his shirt sleeves... It is a mystery to me how he was not missed by the others.

Joseph Moore, Relief Keeper, Letter to the NLB, 28 December 1900Why One Coat on the Peg Matters

In December on the Atlantic edge, you don’t choose to go out coatless. Two sets of oilskins were gone. One hung indoors. That single fact has been in the official file from the start.

Whose coat was left?

The relief accounts and the superintendent’s report identify the men on duty as Principal Keeper James Ducat, Assistant Keeper Thomas Marshall, and Occasional Keeper Donald MacArthur. Marshall had been fined in a previous gale for losing equipment (worth noting because it speaks to his caution about gear). If something on the landing was at risk of being torn away, he and Ducat had motive to go out in their sea kit to secure it. MacArthur, the occasional keeper, may have stayed inside to keep house or act as a runner between lamp checks and the landing. The hanging coat points to him as the one who went out at speed without dressing for the weather.

What prompts a man to run outdoors in winter without his coat? A warning, a shout, a crash from outside, or a surge of water seen coming in. A rogue wave can appear on a rising sea with no time to spare. The choice becomes simple. You move now, or watch two colleagues get swept.

No romance in this reading. Just practical. Two men were working the landing. A third, hearing trouble, ran to help. All three met a line of water that reached higher than any of them expected and took the lot off the rock.

Anatomy of a Rogue Wave Strike

-

~200 feet (60 metres): Clifftop

Turf ripped from the island's summit, 10 metres from the cliff edge. Evidence that solid 'green water', not just spray, crested the island.

-

~110 feet (34 metres): West Landing Path

A heavy wooden supply box was smashed and its contents scattered. Iron railings were bent, and a lifebuoy was torn from its mountings.

-

Sea Level

Base of the cliff. A powerful Atlantic swell, focused by a narrow geo, was likely amplified into a wave of catastrophic height.

The Official Verdict – an ‘Extra Large Sea’

Superintendent Robert Muirhead reached the island on 29 December and took statements from Captain Harvie, his officers, Joseph Moore, and the man who had held the light ashore, gamekeeper Roderick MacKenzie. He examined the landing, noted the missing gear and bent railings, and compared all of it with the routine recorded up to the morning of 15 December.

On Monday, 8 January 1901, he submitted his report. The chain of reasoning runs clear. Two men had dressed for heavy weather and gone to the west landing. The landing showed marks of violent seas. The light went dark on the night of 15 December. Therefore, the men were at the landing on the afternoon of the 15th and were taken by an exceptional wave. Muirhead called it an ‘extra large sea’ and added one key inference. The missing coat most likely means MacArthur rushed out from the lighthouse to warn or assist the others just as the sea struck above them.

A modern reader might look for a Board of Trade hearing or a police file. There’s no sign of either. The Northern Lighthouse Board handled the matter as an internal accident investigation. Deaths by misadventure were registered. Bodies were never recovered. The authorities saw no evidence of foul play.

Official Conclusion: 8 January 1901

I am of the opinion that the most likely explanation of this disappearance of the men is that they had all gone down on the afternoon of Saturday, 15 December to the West landing to secure the box with the mooring ropes etc. and that an unexpectedly large roller had come up on the island, and a large body of water going up higher than where they were, had come down with immense force and swept them away.

Superintendent Robert Muirhead, Northern Lighthouse Board

The Making of a Myth

Two fictions created most of what people now ‘remember’ about Flannan.

First, in 1912, the poet Wilfrid Wilson Gibson published ‘Flannan Isle’, a ballad that imagined the scene as eerie and sudden. Second, in 1929, an article in True Strange Stories printed what it claimed were the keepers’ final log entries. That piece had a man crying, another praying, and a line that read ‘God is over all’.

None of that appears in the 1900 record. The lighthouse log never contained those lines. The poem is a poem. The 1929 ‘logbook’ is a hoax.

How did they take over the story?

They gave readers a feeling. They made the scene indoors. They suggested fear in the room, not danger on the rock. Newspapers at the time had already floated wild ideas – sea monsters, foreign kidnappers, a ghost ship. Later writers lifted from the poem and the pulp piece and passed the drama along. Over time, the counterfeit details felt truer than the plain report. That’s how legend overwrites a file.

Myth versus record, item by item

- Uneaten meal on the table: the relief keeper found a cleaned kitchen. No food on plates. Pots washed and put away.

- Overturned chair: not in any 1900 description. The station interior was in order.

- Terrified log entries: invented in 1929. The real log and slate end with routine remarks up to 9 a.m. on 15 December.

- Days of supernatural storms before the 15th: the meteorology of 12-14 December doesn’t show such a pattern. The 15th did bring a gale.

One more point. The way the myths spread tells us something. A literary image and a false ‘document’ carried more weight in the culture than the administrative report. That’s the narrative fracture at the core of this case.

The Making of a Myth

-

December 1900

The Disappearance

Three keepers vanish. The official investigation finds evidence of a catastrophic wave but no signs of foul play. The record is factual but incomplete.

-

January 1901

The Official Explanation

Superintendent Muirhead's report concludes the men were swept away by an 'extra large sea'. This remains the evidence-based explanation.

-

1912

The Poetic Myth

Wilfrid Wilson Gibson's poem 'Flannan Isle' invents the enduring images of an uneaten meal and an overturned chair, adding a sense of sudden indoor panic.

-

1929

The Logbook Hoax

An article in 'True Strange Stories' publishes fabricated log entries describing crying, praying keepers. These are still quoted as fact, despite being a proven fiction.

Sources

Sources include: official contemporaneous records from the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) archives, including the 26 December 1900 telegram from Captain James Harvie, the 28 December 1900 letter from relief keeper Joseph Moore, and the 8 January 1901 investigation report by Superintendent Robert Muirhead; modern historical analysis debunking later myths, notably the work of Mike Dash on the fabricated logbook entries; contextual maritime records, such as the log of the steamer SS Archtor for the night of 15 December 1900; literary and media sources responsible for the myth, specifically Wilfrid Wilson Gibson’s 1912 poem ‘Flannan Isle’ and a 1929 article in True Strange Stories; and modern meteorological and oceanographic reanalysis of the 1900 storm conditions.

What we still do not know

- What immediate trigger caused Donald MacArthur to run from the lighthouse without his oilskins.

- Why the experienced keepers broke regulations by leaving the lighthouse completely unmanned at the same time.

- The precise nature of the wave, or waves, that caused catastrophic damage more than 200 feet above sea level.

- Why the bodies of the three keepers were never recovered, even on nearby shores in the weeks that followed.

- Whether the keepers' slate, containing the final routine entries from the morning of 15 December, survives in an archive.

Comments (0)