The most famous piece of evidence from the Flannan Isles mystery is the lighthouse log, with its image of men in terror. One crying, others praying, and the final cryptic line, ‘Storm ended, sea calm. God is over all’. That log never existed. It was fabricated in 1929 for an American pulp magazine, almost certainly written by a respected journalist for about two cents a word. This is not the story of vanished lighthouse keepers, but of the factory that built a lie.

This is one part of a multi-part case file. Return to the main Flannan Isles Legacy investigation to see all related articles.

The Economics of Sensation

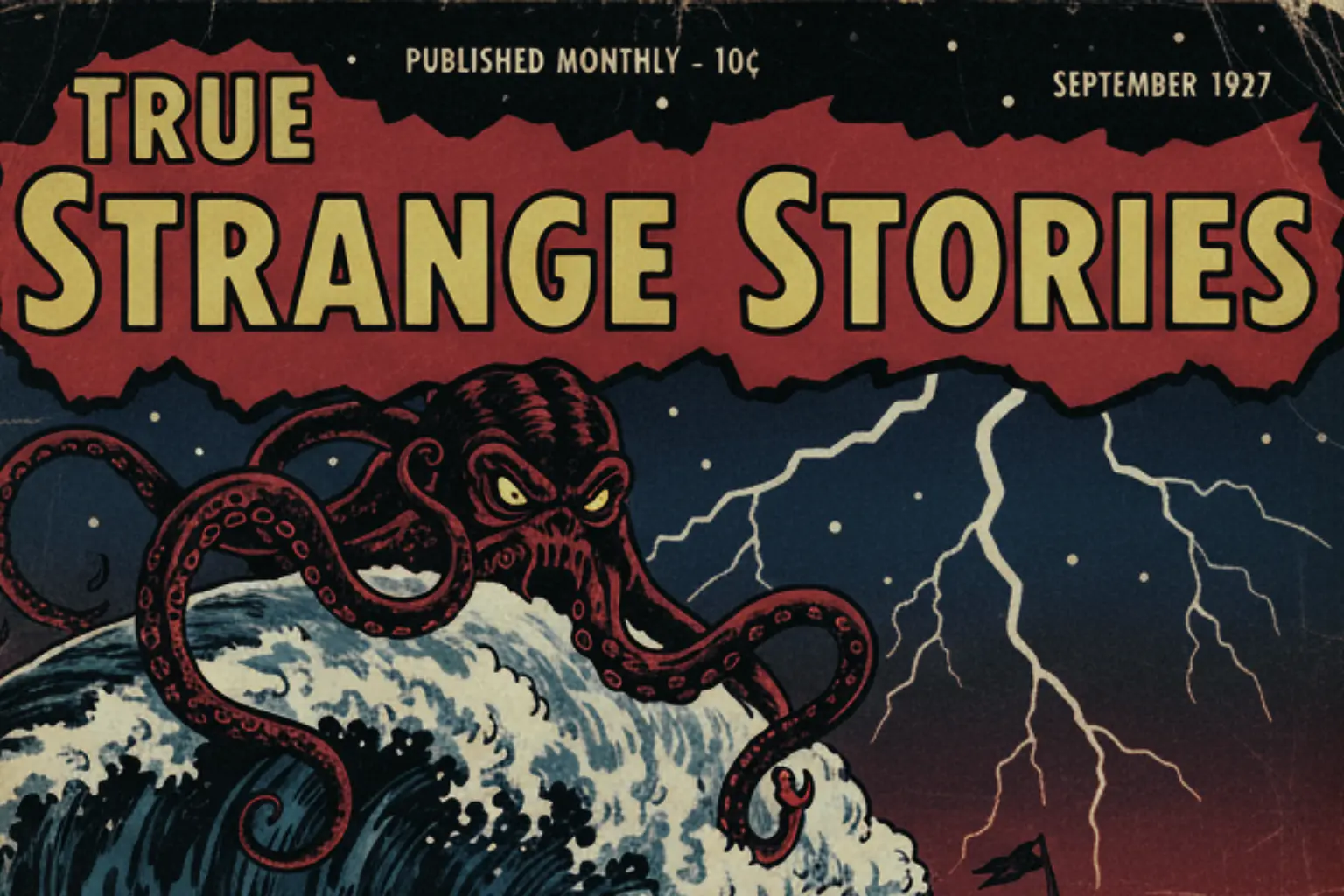

In the 1920s and 1930s, American pulps ran on a high-volume, low-margin model. Interiors were printed on coarse, high-acid wood pulp paper because it was cheap. Covers were glossy and lurid because cover art had to win a fight on crowded newsstands.

Most revenue came from sales, not adverts, so every issue had to shout to move units. At peak, a leading title could push up to a million copies an issue at 10–25 cents, which explains the pressure to deliver reliable thrills every month. The paper itself aged quickly, yellowing and becoming brittle within years, so the product was disposable by design. The format rewarded speed and spectacle.

Pay typically sat at one to two cents per word. A 60,000-word issue might cost a publisher around 600 dollars in 1939 for the entire slate of stories. Writers who needed to pay rent had to be prolific, sometimes turning out thousands of words a day and doing it under multiple pen names to fill a single issue. Upton Sinclair’s reported 8,000 words a day is a useful yardstick for the pace expected when the meter was running. Quantity was the point, not slow archival work.

Research is time-hungry and therefore expensive. Checking maritime logs, weather records, or institutional correspondence takes hours that a penny-a-word writer could not afford. In this system, invention was efficient. You could lift a real headline, strip away the dull bits, add set-piece moments, and hand in copy on time. Real events are often messy and inconclusive; a fabricated scene can be engineered to match the magazine’s promise. Under these incentives, factual accuracy was not a virtue. It was a cost.

Once a magazine had to sell on the strength of the cover and the first page, a neat story beat a complicated truth. Editors needed predictable drama to keep a million-copy machine fed. That system did not merely tolerate embroidery; it made embroidery the rational choice. Lies were faster to make, easier to package, and more likely to be bought by the editor and the reader.

The high-acid paper was never designed for an archival life, which mattered. If the physical stock decays fast, only the most repeatable narratives survive, and those tend to be the simple, dramatic ones that later writers keep copying. The material culture of the industry mirrors its editorial choices of disposable pages and durable myths. That commercial pressure set the stage for Bernarr Macfadden’s most profitable idea.

The Pulp Profit Engine

A typical 1930s publisher's balance sheet shows why invention paid better than fact.

Low Production Cost

Approximate total cost for all written content (60,000 words at 1 cent per word) in a single issue.

High Volume Revenue

Potential gross revenue from a successful issue selling one million copies at 10 cents each, before distribution and printing costs.

The Financial Incentive for Fabrication

With a potential 166x return on content spend, the financial pressure to prioritise cheap, sensational fiction over slow, costly research was immense.

The ‘True Story’ Formula

In 1919, the publisher and physical culture impresario Bernarr Macfadden launched ‘True Story’, a magazine built on first-person confessions and marketed under the motto ‘Truth Is Stranger Than Fiction’.

It drew on real letters sent to his ‘Physical Culture’ magazine and turned that material into a new commercial genre. By 1929, circulation neared two million, which shows how well the formula worked with a working-class readership that disliked the moralising tone of the ‘slicks’. The brand promise was authenticity, but the aim was scale.

Pieces were framed as first-person letters from ordinary readers, edited to sound like unguarded talk. The template did not stay put. Macfadden rolled it into sister titles such as ‘True Romances’ (1923) and ‘True Detective Mysteries’ (1924), then extended the approach with ‘Ghost Stories’ (1926).

In 1929, the model turned to the uncanny with ‘True Strange Stories’, applying the same first-person staging to claims of the supernatural. The setup primed readers to take an ‘I was there’ voice as reportage.

Macfadden did not rely on drawings. He used posed studio photographs of actors to illustrate confessions and mystery pieces, which made the pages read like file shots from a case. That choice blurred boundaries. A tearful face under a headline looks like evidence at a glance, even when it was staged. The visual rhetoric did a lot of the work.

The ‘True’ label spread as a house style and a promise, creating a family of titles that felt like journalism to casual readers. That made the model easy to port, including to the paranormal. Once you train an audience to accept a first-person confession as documentary, swapping ‘I sinned’ for ‘I saw a ghost’ is a small step.

The word ‘True’ on the masthead acted like a badge of verification when none existed. In practice, it was branding.

The content pipeline was entertainment. That is the critical frame for the Flannan Isles forgery. The house style delivered emotional proximity and a veneer of reality before a reader hit the second paragraph. Which leaves the question, who was writing these ‘true’ pieces, and under what names?

The Assembly Line of Authorship

Pulp authorship was industrial, and pseudonyms were normal. Many writers used several pen names in a single issue to make one person look like a stable of contributors. That practice served a business need. It lets editors fill pages without giving any one writer too much leverage on the rate. It also left historians with a tracking problem, because the same pair of hands can hide under half a dozen names.

Because the pay was low and deadlines were frequent, a fast writer could supply entire sections of a magazine under different signatures. Readers saw variety; the ledger showed one cheque. In that world, discovering the true author of any given ‘true’ story can be a genuine research problem. The mask was part of the machine.

A ‘house name’ is a pseudonym owned by the publisher. The signature stays the same even when the human behind it changes. Famous examples include ‘Maxwell Grant’ on ‘The Shadow’, used as a brand while Walter B. Gibson did the writing, and ‘Kenneth Robeson’ for ‘Doc Savage’. The point was continuity and control. Characters belonged to the company, not the writer.

Once signatures were interchangeable, the writer became a replaceable component. That fits the economics set out above. It also matters for this case because the byline ‘Ernest Fallon’ in 1929 may be a single-use mask rather than a person who published under that name again. The system was built to make such masks.

If a business model hides authors and owns names, fabricated ‘documents’ can circulate without a clear maker to question. The structure normalised anonymous authority. That is the environment in which a fake lighthouse log could pass as credible for readers and later authors.

The 'House Name' Assembly Line

A publisher-owned pseudonym allowed multiple, interchangeable writers to produce content under a single, consistent author brand.

The publishing house (e.g., Street & Smith) legally owned the character and the author's name.

A fictional byline (e.g., 'Maxwell Grant') was created. This name appeared on every story.

A primary writer (e.g., Walter B. Gibson) and other interchangeable ghostwriters were hired to write the stories, all of which were published under the house name.

The Flannan Isles Record: A Scene of Order

The Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) record gives us a clean anchor. We have Captain James Harvie’s telegram of 26 December 1900, relief keeper Joseph Moore’s letter of 28 December, and Superintendent Robert Muirhead’s formal report of 8 January 1901. These documents set out what was found and what the Board concluded.

Before looking at the pulp account, we fix this baseline.

Harvie wired: ‘A dreadful accident has happened at Flannans. The three keepers, Ducat, Marshall and the occasional have disappeared from the island’.

He noted stopped clocks and suggested a working theory. The men were blown over the cliffs or drowned while trying to secure a crane or similar. It is a practical line from a working captain. No supernatural framing.

Moore found the kitchen fire had not been lit for days. The beds were empty ‘just as they left them in the early morning’. Lamps had been refilled. He then documented severe storm damage at the west landing, including broken railings and a missing rope box on the incline. Inside was routine. Outside was violent. That contrast matters.

Muirhead confirmed Moore’s observations and added detail. ‘The pots and pans had been cleaned and the kitchen tidied up’, which shows the cook finished his job. He logged a dislodged stone over a ton in weight thrown onto a path about 110 feet above sea level, a concrete measure of the sea’s force. His conclusion was plain… while securing gear at the west landing on 15 December, an ‘unexpectedly large roller’ (a powerful, unusually large wave) swept the men away.

Across three documents in two weeks, the picture is consistent. Tidy interior, heavy weather outside, a plausible accident. There is no mention of an uneaten meal, no overturned chair in any Board paper, and no emotional log book entries. This is the record against which all later stories should be measured.

Fact vs. Fiction: The Flannan Isles Record

| The Popular Myth (Post-1912) | The Official Record (Jan 1901) |

|---|---|

| A meal of meat, cheese, and bread was left uneaten on the kitchen table, suggesting a sudden interruption. | The kitchen was found tidy, with 'pots and pans cleaned', indicating the cook had finished his duties. |

| An overturned chair was discovered, implying a struggle or sudden panic. | No mention of any disarray or overturned furniture inside the lighthouse. The station was described as orderly. |

| A fabricated logbook detailed a supernatural storm, with keepers crying and praying in terror. | The log contained only routine entries about weather and duties. There was no emotional or unusual content recorded. |

The details that define the modern myth were introduced in a 1912 poem and a 1929 pulp magazine, contradicting the official findings of the Northern Lighthouse Board.

The Forgery: Manufacturing Terror in Print

Twelve years on, in 1912, poet Wilfrid Wilson Gibson published ‘Flannan Isle’. He introduced two images that stuck, a dinner ‘all untouched’ and a chair ‘tumbled on the floor’. The poem is strong on atmosphere, which is why those lines keep being quoted. It is also fiction. The NLB kitchen was clean and tidied. Gibson’s rhetorical choices are the first pivot away from the file.

Seventeen years later, in August 1929, ‘True Strange Stories’ ran a piece under the one-off pseudonym ‘Ernest Fallon’ that introduced a ‘log’ full of tears, prayers, and that final ‘God is over all’ line.

Meteorological records do not support the multi-day storm described. The emotional tone is tailored to the Macfadden confessional house style. This is the first appearance of the text quoted ever since. The document never existed in 1900. It was made to order in 1929.

The pulp log has James Ducat ‘very quiet’, the tough Donald McArthur ‘crying’, and the men praying.

The last entry reads: ‘Storm ended, sea calm. God is over all’. It is a perfect closing beat for a magazine story. It is also incompatible with the NLB paperwork and the known state of the kitchen. The tension between those two streams tells you which pipeline you are reading.

Fabricating a ‘primary document’ inside a story is a powerful way to stabilise a hoax. Readers are trained to trust logs and reports inside a magazine with ‘True’ on the cover, the effect multiplies. A writer who knew the rhythms of official prose could mimic the voice and carry the reader past doubt.

Gibson’s poem is art. The 1929 log is a counterfeit, inserted to convert a tidy accident into an eerie legend that could be sold as reportage. That is the line where the case leaves the archive and enters the hoax factory.

‘December 12: Severe winds, the like of which I have never seen... James Ducat is very quiet. Donald McArthur crying... December 15: Storm ended, sea calm. God is over all’.

The 1929 Forgery – Invented for ‘True Strange Stories’ MagazineUnmasking the Forger: A Journalist’s Skills

The byline ‘Ernest Fallon’ appears to be a one-use pen name. In the same 1929 ‘True Strange Stories’ issue, there is a signed John L. Spivak piece, and there are items under other signatures known to be Spivak’s pseudonyms, including ‘Howard Booth’ and ‘Paul Dinsmore’.

That pattern makes Spivak the leading suspect for ‘Fallon’. It fits the single issue cluster and his habit of writing under several names in one number.

The evidence is not a confession; it is a set of overlaps. Spivak is present in the Macfadden ecosystem at the exact moment. He publishes in that issue. Two other names in the table of contents are documented aliases tied to him. Add the known industry habit of masks and house names and the path from Spivak to ‘Fallon’ becomes plausible. That is as far as the record goes, and it is enough to understand the craft involved.

Spivak was a muckraker, an investigative journalist who exposed corruption, known for investigations into chain gang brutality and the early shape of American fascism. He knew how official prose looks and how to structure a document that reads like a file. That is exactly the skill a fabricator needs if the goal is to mint a convincing ‘log’.

The same competencies used to expose a prison abuse scandal can be inverted to write a page of fake lighthouse routine with a human touch. That inversion is the uncomfortable lesson here. A professional who can sound like a report can also forge one for a fee when the market rewards it.

If a respected investigative journalist likely forged the most cited ‘document’ in the Flannan case, the hoax is not a clumsy fan tale. It is a professional product shaped to a brand that sold millions of copies a month. That is the scale of the operation that overwrote the record.

‘Spivak was known for his hard-hitting exposés on topics like the brutal conditions of Georgia chain gangs and the rise of fascism in America... a master of the documentary style’.

Syracuse University, John L. Spivak PapersThe Viral Hoax: How a Lie Becomes Legend

The pulp magazine page does not last. The story does. Once a punchy version exists, later writers copy it, then cite each other, and the origin melts away. That is the laundering process, repeated citation that strips origin. It is how a forged ‘log’ migrates from a ten-cent magazine into a hardback ‘non-fiction’.

In 1965, Vincent Gaddis published ‘Invisible Horizons: True Mysteries of the Sea’ and retold the Flannan tale with the fake log entries included. He cited the 1929 ‘True Strange Stories’ article as his source. Gaddis was already influential in the mystery space and later coined the term ‘Bermuda Triangle’. His stamp moved the pulp lies into a new tier of credibility.

Once Gaddis printed the log as if it were a real historical artefact, subsequent books, articles, documentaries, and websites repeated it. The NLB’s tidy kitchen and Muirhead’s roller do not make good television. The prayer line does. Over time, copy and paste retellings assembled a canon where the forgery became the ‘fact’ and the archive footnotes vanished.

The Flannan case shows a four-stage method that can be applied anywhere. Mine a real event, strip out the dull, inconvenient parts, insert confessional beats and a fabricated primary document, and publish it under a brand that promises truth. Later authors launder it by citation. That is the hoax factory.

A 1901 official conclusion was replaced by a 1929 magazine invention, then canonised in 1965 for mass audiences. The commercial pipeline turned a workplace accident into modern folklore.

The Hoax Laundering Process

The 1901 Northern Lighthouse Board report concludes a tragic, but entirely natural, accident occurred.

In 1929, 'True Strange Stories' magazine invents a sensational logbook to create a supernatural mystery for profit.

Vincent Gaddis's 1965 book cites the pulp magazine as a legitimate source, giving the forgery a new layer of credibility.

Later authors, documentaries, and websites repeat the story, citing Gaddis or each other, until the forgery becomes the accepted 'fact'.

Sources

Sources include: primary historical documents from the Northern Lighthouse Board concerning the Flannan Isles incident of December 1900, including Captain James Harvie’s initial telegram and Superintendent Robert Muirhead’s official report of January 1901 ; the foundational texts of the myth, including Wilfrid Wilson Gibson’s 1912 poem ‘Flannan Isle’ and the August 1929 issue of True Strange Stories which introduced the fabricated logbook ; historical analysis of the American pulp magazine industry, its economic model, and publishing practices from academic sources and primary records from the Pulp Magazines Project ; archival records from Syracuse University on the life and work of investigative journalist John L. Spivak ; and published works and modern analysis tracing the forgery’s transmission, including Vincent Gaddis’s 1965 book Invisible Horizons: True Mysteries of the Sea and research by historian Mike Dash.

What we still do not know

- Whether ‘Ernest Fallon’ can be tied to a living person with archival proof, or whether a publisher-owned mask was used for a one-off hoax.

- If a complete, verifiable copy of the August 1929 ‘True Strange Stories’ issue can be located with full production notes that confirm authorship.

- The exact editorial pathway that approved the fabricated log text inside Macfadden’s shop, including who signed off content that mimicked an official document.

- How many other ‘true’ paranormal pieces from the 1920s–30s contain forged ‘primary’ documents that later migrated into non-fiction books.

Comments (0)