In the twelfth century, Hildegard of Bingen compiled a list of 1,011 coined words she said came by vision. Scholars long treated it as a devotional curiosity or a private code. Yet the only place those words appear in running text is a short Latin hymn that uses five ‘unknown’ terms, and four of the five are missing from the 1,011-word list. If the list was complete, where did the missing forms come from? That contradiction is the hinge of this inquiry.

The Abbess and the ‘Unknown Language’

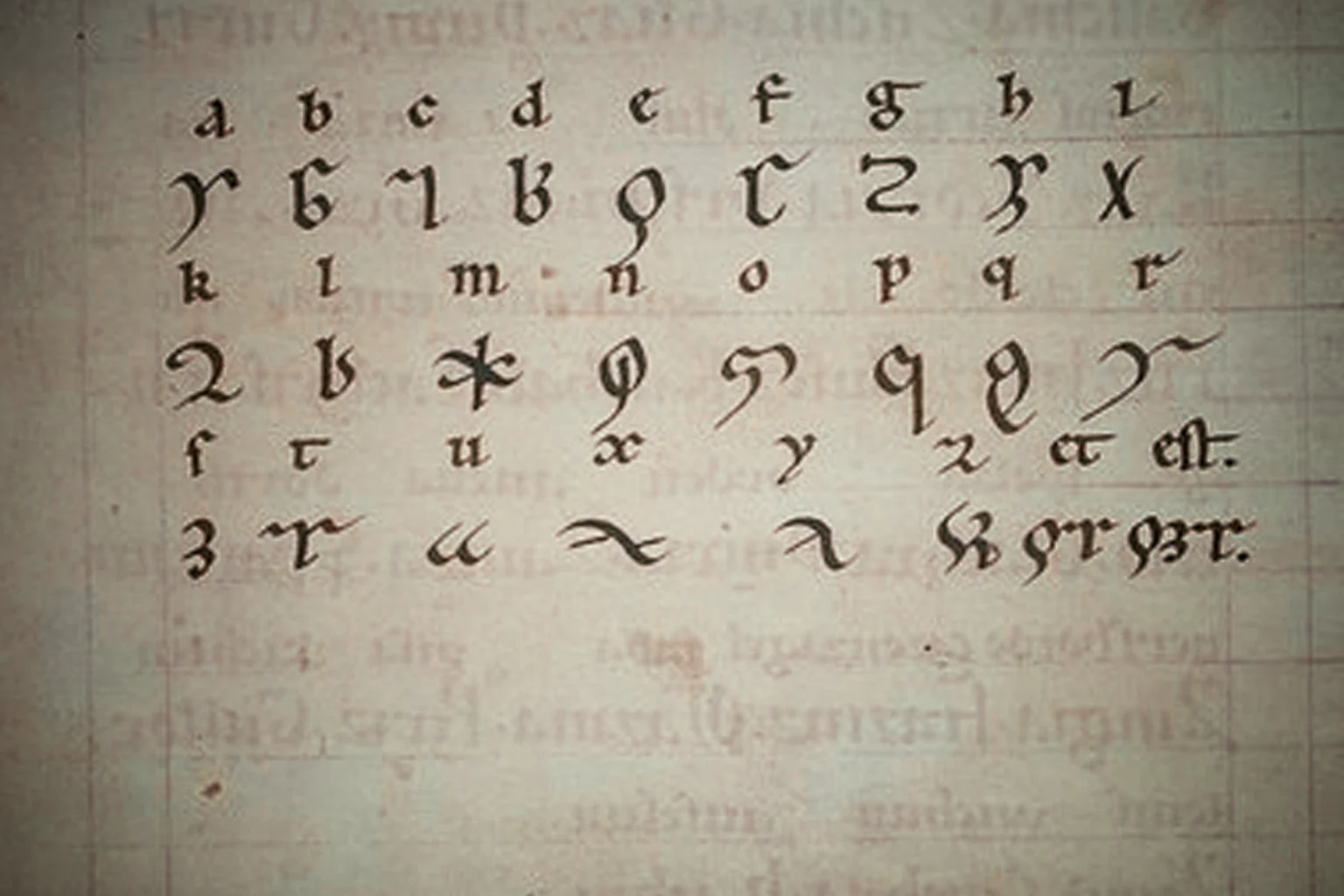

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) led a women’s community first at Disibodenberg, then at Rupertsberg near Bingen, Germany, after approval of her writings in 1147. Between about 1150 and 1158, she devised two linked artefacts. She called the vocabulary her ‘lingua ignota’, a list of roughly 1,011 coined words, mostly nouns, each glossed into Latin and sometimes Middle High German. Alongside it, she used the ‘litterae ignotae’, a 23-letter alphabet aligned with contemporary Latin practice and lacking j, v and w; several letterforms echo Greek or Roman cursive hands.

Earliest traces sit within a tight window.

Around 1153, she wrote to Pope Anastasius IV and described the language as a miracle. In the same period she wrote a letter to the monks of Zwiefalten and rendered their names in the new alphabet. By 1163, she was naming both the ‘lingua ignota’ and the ‘litterae ignotae’ in the preface to Liber Vitae Meritorum, which shows she considered them part of her public work rather than a private diversion.

In a short chant, ‘O orzchis Ecclesia’, she inserts several of the coined words into otherwise Latin sentences, letting Latin carry the grammar while the new nouns supply meaning in place of Latin terms. That is relexification in practice, where new vocabulary rides on an existing language’s syntax.

Hildegard & the ‘lingua ignota’ timeline (1098–1949)

-

1098

Birth at Bermersheim, Germany

Begins the life arc that frames the language project.

-

1136

Elected magistra at Disibodenberg

Leadership role preceding the move to Rupertsberg.

-

1147

Approval of her visionary writings

Recognition that helps establish authority for later work.

-

1150

Founds Rupertsberg near Bingen, Germany; becomes abbess

Institutional base for writing, music, and the language project.

-

c. 1150–1158

Compiles the ‘lingua ignota’ and adopts the ‘litterae ignotae’

Glossary of c. 1,011 coined words with a 23-letter alphabet aligned with Latin practice.

-

1153–1154

Zwiefalten letter in the new alphabet

Names of monks rendered using the ‘litterae ignotae’.

-

c. mid-1150s

Chant ‘O orzchis Ecclesia’ composed

Latin lines embed five coined words; four are absent from the copied glossary.

-

1163

Preface to Liber Vitae Meritorum names language and alphabet

Places the project on the public record.

-

1170

Volmar warns the ‘unheard language’ may pass with her

Suggests no wider speech community formed around the lexicon.

-

1179

Death at Rupertsberg

Closes the authorial window; preservation depends on copyists.

-

c. 1180–1200

Riesencodex (Wiesbaden Hs. 2) compiled; Berlin abridgement

Primary witnesses preserving the glossary and alphabet.

-

c. 1800–1830

Vienna copy disappears from the record

Loss of a witness that may have carried variants or notes.

-

1949

Riesencodex secured in Wiesbaden holdings

Modern custody consolidates access to the most complete record.

Two Manuscripts and a Single Hymn

Everything we can inspect comes from two medieval witnesses and one hymn.

The Wiesbaden Riesencodex (Hs. 2) preserves the most extensive list and the alphabet. The Berlin manuscript (Lat. quart. 674) holds an abridged list with small differences. A third copy, once noted in Vienna, vanished between about 1800 and 1830. The loss matters because the surviving copies behave like working compilations rather than a canonical edition, variants or notes may have sat in the missing witness.

The list is thematic. It descends from divine beings to humans, ranks of kin, animals, plants and tools. Entries are glossed into Latin and sometimes Middle High German. There is no separate grammar tract, no set of rules for agreement or verb formation, and no continuous text written wholly in the new words.

The hymn is the sole connected context. It embeds five forms inside two Latin sentences. A short analysis helps readers audit the claim.

‘O orzchis Ecclesia’ - the five inserted forms

- orzchis: not in the 1,011-word glossary; behaves adjectivally within the Latin line.

- caldemia: not in the glossary.

- loifolum: from ‘loifol’ ‘people’; a Latin genitive plural ending attached to a coined stem.

- crizanta: not in the glossary.

- chorzta: not in the glossary.

Why this matters: four of the five are absent from the copied list; either the working vocabulary was larger than 1,011 items or performance minted forms that copyists never entered into the glossaries.

Those missing forms are the lever, they force the larger question of what this system really is.

Simple Code or Complex Creation?

The received view calls the lingua ignota a glossary with no grammar, useful as a cipher or as devotional colour. The physical form backs that. We have a list, glosses and an alphabet; the connected text is a Latin hymn with a handful of inserted words.

Two elements strain the simple code reading.

First, scope: The list attempts breadth, from God and angels through kin ranks, body parts, tools, birds and trees. That exceeds the needs of a small cipher lexicon.

Second, structure: Within the list we find consistent building blocks. Pairs such as ‘peueriz’ ‘father’ and ‘hilz peueriz’ ‘stepfather’, or ‘phazur’ ‘grandfather’ and ‘kulz phazur’ ‘ancestor’, show productive morphemes, that is, recurring prefixes with stable meanings. Tree names often end in ‘ buz’. Invented nouns tend to align with the grammatical gender of their Latin glosses. The parts of the system behave like a designed naming scheme rather than a loose bag of ciphers.

A cautious label is useful here. The material looks like a constructed language in embryo: a planned vocabulary with internal patterns, intended to work inside Latin syntax rather than replace it. In practice, it behaves like re lexification, with Hildegard’s coinages standing where Latin nouns would normally stand.

One limit governs all claims: there is no surviving grammar treatise from Hildegard’s hand. That absence does not prove she had none, but it caps what can be inferred.

Working theories tested against evidence

Theory A: simple glossary and codebook.

The physical form is a list with glosses, not a grammar. The only connected text is a hymn that borrows Latin grammar and uses a handful of new terms. A small cipher lexicon could serve to hide names or add sacred colour to performance. The Zwiefalten letter, which encodes names, fits. The lack of dialogue or prose supports a narrow, situational use.

Counter pressure: A cipher list does not need a thousand entries. Nor does it need stable compounding across categories. The architecture looks planned.

Theory B: proto conlang on a Latin chassis.

Hildegard designed an alphabet. She built a lexicon with internal building rules. She aligned genders with Latin glosses. In context, her words take Latin endings, as ‘loifolum’ suggests. This profile fits an early, partial constructed language whose words were meant to be used inside Latin syntax. It accounts for the hymn, the patterns and the list’s breadth. It cannot show an independent syntax or verbs. The corpus limits the claim; it does not falsify it.

Theory C: statistical artefact, no real depth.

Order can arise because an editor imposes order. Power law-like curves at the character level can emerge from consistent coinage habits. On this view, the signals are by-products of presentation.

The difficulty is accumulation: the same hand that lays out sections also invents families of words with shared affixes and sound motifs, and those choices persist. That is less like accident and more like design.

Central contradiction: two readings tested

| Evidence axis | ‘Simple glossary / codebook’ | ‘Proto-conlang on a Latin chassis’ |

|---|---|---|

| Form of corpus | List with Latin glosses; one token per type; no grammar tract. | Same corpus accepted, read as a designed lexicon intended to sit inside Latin syntax. |

| Use evidence | Names encoded in the Zwiefalten letter; occasional display use. | Hymn inserts coined nouns while Latin carries grammar; behaviour fits re-lexification. |

| Scope of lexicon | Large but unnecessary for a basic code; size treated as surplus. | Broad, near-encyclopaedic ambition expected for a naming system. |

| Internal structure | Regularities seen as editorial convenience or house style. | Productive morphemes: ‘hilz-’, ‘kulz-’, tree suffix ‘-buz’; gender aligns with Latin glosses. |

| Statistics | Character skews and clustering are by-products of list ordering. | Non-uniform character distribution and thematic clustering indicate design choices. |

| Predicted behaviour in hymn | Occasional colour terms; forms need not match a larger system. | Coined stems take Latin endings in context (e.g., ‘loifolum’), as expected. |

| Limits | No sentences fully in the new words; no grammar book. | Same limits admitted; absence of grammar caps claims to a constructed lexicon, not a full language. |

| Best label | ‘Glossary with code uses’. | ‘Constructed lexicon intended for Latin syntax’. |

Rows summarise how each reading fits the evidence.

How the Debate Shifted

Positions over time shape how people read the evidence.

Nineteenth-century editors tended to cast the material either as an ideal or universal language or as a curiosity, sometimes reacting to frank anatomical vocabulary rather than to structure.

Modern mainstream work treats it as a secret or sacred language used inside Latin. Sarah L. Higley argues for a personal artistic language with real derivation rather than ecstatic speech. Jeffrey T. Schnapp reads it as an Edenic naming project that tries to start language afresh. Jonathan P. Green emphasises the prophetic frame and the way the manuscripts tie the list to Hildegard’s authority.

The range runs from cipher to sacred naming, but all serious treatments pay attention to the internal patterns and to the narrow corpus problem.

‘An intellectual diversion on a level with crossword puzzles’

Sabina FlanaganA Statistical Profile of the Abbess’s Code

A glossary cannot show the usual rank by frequency curve that long texts do, the pattern often called Zipf’s law, because each item appears once by design. We can still look at structure below the word level and at characters.

Thematic clustering: Words and sub morphemes cluster by topic. The tree ending ‘ buz’ sits almost entirely in the trees section. Prefixes linked to kinship repeat within the family group. The clustering is not an emergent property of a running text; it is the declared order of the list, and it survives simple statistical checks.

Character distribution: At the character level, the 23 letters show a non-uniform spread consistent with an intentional palette. There is a visible skew toward certain consonant shapes, including those written as ‘z’, ‘x’ and ‘sch’. That is what deliberate coinage tends to leave, though letter counts alone do not prove a phonological system.

Information entropy: We measured unpredictability at the character level. Values sit between the flatness of random strings and the rigidity of simple substitution codes. For context on language like statistical behaviour in medieval enigmas, see the PLOS ONE study on the Voynich Manuscript. That is consistent with design. It is not proof of a spoken language or a hidden grammar.

Taken together, these measures undermine the ‘purely simple’ reading. They do not conjure a lost grammar. They show a built lexicon with consistent internal choices.

Voynich as a comparator

The comparison helps in one way and misleads in another.

Helpful: Both artefacts show non-random structure. Voynich displays language like word distributions in long text. The lingua ignota displays a designed network in a list. This shows that profiling can reveal signals in opaque material.

Misleading: The corpora differ. Voynich offers thousands of tokens for word-level analysis. Hildegard offers one token per type, plus five in a hymn. A clean Zipfian curve across words in the lingua ignota would be an artefact. The right comparisons sit at the level of characters, morphemes and category structure, which is where the present analysis lives.

Even with signals at the character and morphology level, the limits of the record still cap what anyone can claim.

Character entropy (normalised, 0–1)

Normalised character-level entropy. Lingua Ignota clusters with Latin and Middle High German; a random string is higher.

What the Record Fails to Explain

No grammar book: Neither Riesencodex nor Berlin preserves rules for syntax, agreement or verb formation. The absence sets a hard ceiling on claims.

No spoken attestations: There is no dialogue in the new words and no report of routine use in the convent. Volmar’s worry suggests that Hildegard did not establish a community of users.

An incomplete lexicon: The hymn’s out-of-list forms imply a larger working set than the 1,011 entries copied. The Vienna loss deepens the doubt.

Analytical blind spots: Because there is no running text, popular language tests at the word level are not available. Work must sit at the level of characters, morphemes and category structure.

These limits are not decorative. They govern how far intention can be read into patterns. They also point to the next tests worth doing.

If one demands a full grammar to call something a language, Hildegard did not leave one.

The lingua ignota that survives is a lexicon with Latin as scaffolding. That is a hard limit set by the sources. Within that limit, the evidence points to a planned system with derivational patterns, a selected phonology and an encyclopaedic order that tries to rename the world from top to bottom.

The hymn’s ‘missing’ words nudge us to treat the 1,011 word list as a preserved slice rather than a whole. On balance, the Abbess’s Code looks less like a crossword diversion and more like a medieval attempt at engineered sacred naming, executed with craft, then frozen by time into the form we see today.

Sources

Sources include: Cantus Database entry for Wiesbaden, Hochschul und Landesbibliothek RheinMain, Hs. 2 (‘Riesencodex’); the Notre Dame Manuscript Studies post ‘Letter? I ‘ardly know ‘er’ on the Zwiefalten letter; Jeffrey T. Schnapp, ‘Virgin Words’ (Internet Archive scan); Jonathan P. Green, ‘A New Gloss on Hildegard’s Lingua ignota’ (Brepols). Sarah L. Higley, ‘Hildegard of Bingen’s Unknown Language’ (OpenEdition); ‘Keywords and Co Occurrence Patterns in the Voynich Manuscript’ (PLOS ONE) for comparative method; World History Encyclopedia ‘Hildegard of Bingen’.

What we still do not know

- Grammar: no surviving treatise; any rules for syntax or agreement are unrecorded.

- Use in speech: no dialogue or routine convent use attested; Volmar implies non-transmission.

- Completeness: hymn-only words suggest a larger working set than the 1,011 entries.

- Lost witness: the Vienna copy is missing; unknown whether it carried variants or notes.

- Morphology scope: whether prefixes/suffixes were fully systematic or local coinage choices.

Comments (0)