A cartographic mystery with geopolitical consequences that continues to haunt Mexico’s maritime claims

On a clear day in March 2009, Mexican researchers aboard the university vessel Justo Sierra cut through the turquoise waters of the Gulf of Mexico. They were sailing toward coordinates that had appeared on maps for nearly five centuries: 22° 33′ N, 91° 22′ W. Their mission was to find an island that should have been unmistakable.

Bermeja Island, with its distinctive reddish shores, wasn’t supposed to be some insignificant speck. Historical records described a substantial landmass, roughly 80 square kilometres, the size of Manhattan.

The Mexican government had urgent reasons to locate it. Billions of barrels of oil, national pride, and territorial rights all hung in the balance.

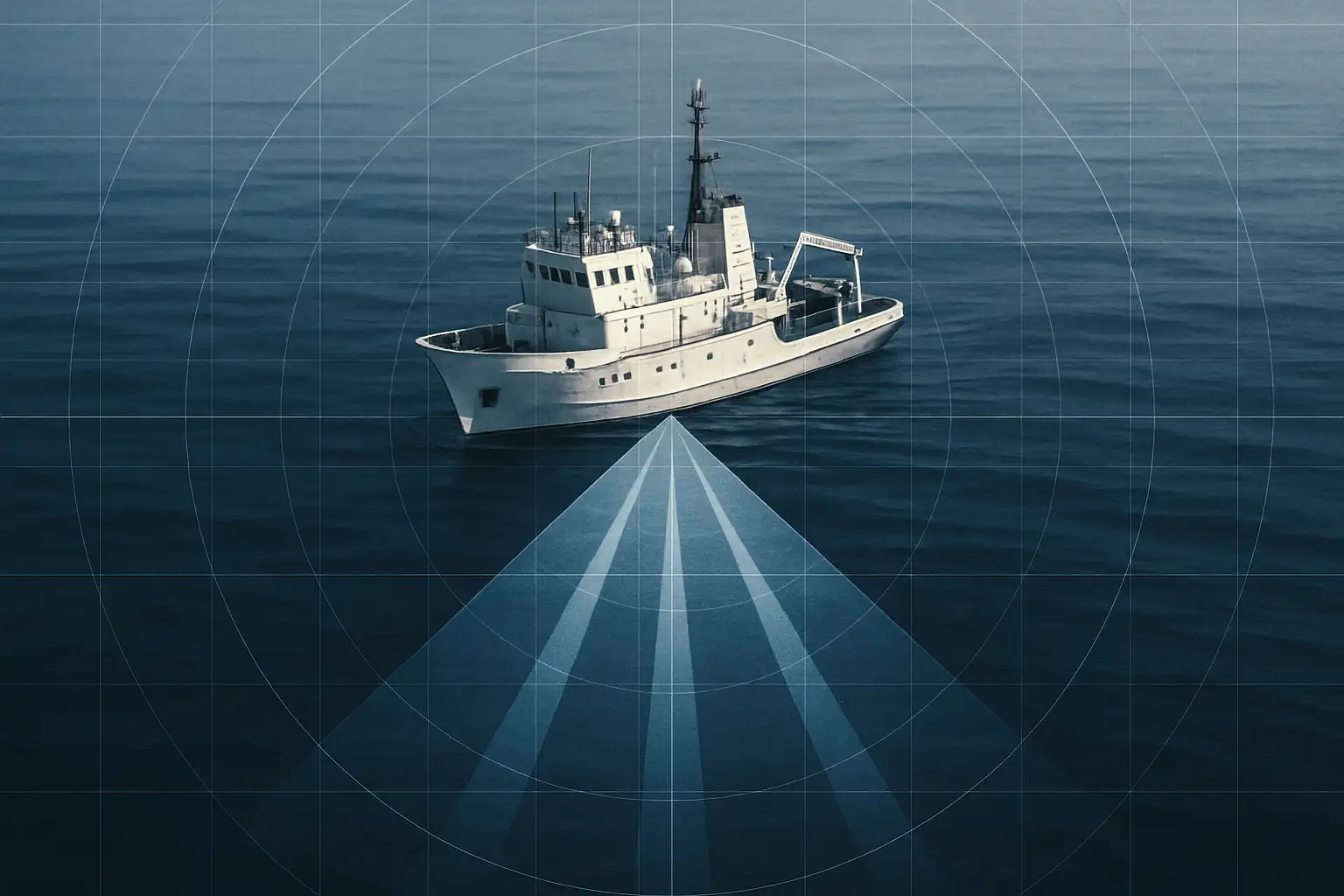

But as sophisticated sonar equipment penetrated the depths, the truth surfaced with cold clarity. There was nothing there. No island. No submerged landmass. Not even a trace that anything resembling an island had existed at those coordinates for at least 5,300 years.

How could something so thoroughly documented by respected cartographers, an island that appeared consistently on maps from 1535 to 1921 simply vanish? Or more unsettlingly had Bermeja ever existed at all?

The Cartographic Birth of Bermeja

How does a non-existent island come to be? The answer lies in the Age of Exploration, when European powers were mapping the New World with quill and parchment, combining scientific observation with necessary imagination as they attempted to chart a vast unknown.

Bermeja first appeared on a Portuguese map from 1535, preserved in Florence’s State Archive. This early representation already attributed a substantial size to the island. 80 square kilometres. It was not a mere rocky outcrop, but a significant landmass.

But it was Spanish cartographers who truly established Bermeja in the geographical record:

- Alonso de Santa Cruz described the island in detail in his 1539 work, El Yucatán e Islas Adyacentes. Santa Cruz noted its distinctive colouration, explaining it was called Bermeja “as it appears to be to such a colour,” referring to the Spanish word for reddish.

- Alonso de Chaves provided remarkably precise coordinates in his Espejo de Navegantes (c.1540): 22° 33′ N latitude and 91° 22′ W longitude. He described Bermeja as a small island that appears “blondish or reddish” from a distance, and meticulously positioned it in relation to other landmarks: “It is to the west quarter to the northwest of the Cape of San Anton, 14 leagues away. It is to the west-northwest of the Alacranes, 55 leagues away.”

This level of specific detail from respected sources established Bermeja not as vague speculation, but as a documented entity with location, colour, and dimension. These descriptions carried the weight of authority. Both Santa Cruz and Chaves were official cartographers of the Spanish Crown, their work used to guide navigation and establish territorial claims.

Once legitimised by these authorities, Bermeja gained cartographic permanence. It appeared on maps by other notable cartographers:

- Sebastian Cabot’s map of 1544

- Abraham Ortelius’s world map of 1564 (spelled “Vermeja”)

- Henry S. Tanner’s map of Mexico in 1846

- The 1858 Mexican Atlas

- The 1921 edition of the Atlas of the Mexican Republic

For nearly four centuries, Bermeja endured on paper. Its reddish shores, never confirmed by direct observation, nevertheless shaped how generations understood the Gulf of Mexico.

Early Questions About Bermeja

Like a ghost that vanishes when directly approached, Bermeja proved elusive whenever anyone tried to confirm its existence. Even as it persisted on maps, troubling inconsistencies began to emerge. Those who actually sailed to its reported location found themselves surrounded by nothing but endless blue.

The earliest known failure to locate Bermeja came in the late 1700s, when New Spain cartographer Ciriaco Ceballos found only open sea where both Bermeja and another island, Not-Grillo, were meant to be. He blamed the original reports on poor visibility and treacherous waters, which often forced 16th-century mariners to map hastily from a distance.

French-Mexican cartographer Michel Antochiw Kolpa later claimed that British maps from 1844 already showed Bermeja as submerged, some 60 fathoms beneath the surface.

Whether or not those charts exist, the 1902 survey by a French naval vessel confirmed one thing: there was no land, no reef, no trace of an island. Newspapers ran with the story, headlining it as “Island Disappears!”, and blamed earthquakes or geological collapse.

Yet despite these failures, Bermeja persisted in official atlases for decades. It was easier to copy than to question.

Oil, Boundaries, and National Sovereignty

What transforms an obscure cartographic footnote into a matter of national urgency? In Bermeja’s case, the answer floats on the sea surface in dark, lucrative pools. By the late 20th century, what was once merely a curious mapping discrepancy had become a potential key to immense wealth and territorial power.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), coastal states can claim an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles from their recognised territorial baselines, including islands. The reported location of Bermeja (approximately 100 miles northwest of the Yucatán Peninsula) was strategically vital.

If confirmed as Mexican territory, Bermeja would have served as Mexico’s northernmost sovereign point in that part of the Gulf, significantly extending its EEZ northwards. In its absence, the Alacranes Islands (Arrecife Alacranes) became Mexico’s furthest undisputed reference point, considerably reducing the reach of its maritime claim.

This directly affected how oil-rich regions in the Gulf, known as the “Doughnut Holes” (Hoyos de Dona), were divided. These are areas of seabed lying beyond the initially clear-cut 200-nautical-mile EEZs of both the United States and Mexico.

The status of Bermeja was a key variable in determining who controlled these potentially lucrative zones.

The economic stakes were immense. Estimates frequently cited potential oil reserves of 22.5 billion barrels in the broader areas under dispute.

For Mexico, access to these reserves would have been a significant boost for its national oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), a cornerstone of the country’s economy and a major contributor to the national budget.

The Treaty That Changed Everything

When nations draw lines across water, they’re often drawing boundaries around fortune itself.

In June 2000, with pens that would shape the economic destiny of both countries, Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo and U.S. President Bill Clinton signed a bilateral treaty establishing maritime boundaries in previously undefined areas of the Gulf of Mexico. This agreement aimed to clarify drilling rights for crude oil, dividing a zone of approximately 17,790 square kilometres.

Crucially, by the time these negotiations concluded, Bermeja Island was “no longer visible” or verifiable. Some Mexican legislators later contended that President Zedillo’s administration was aware of Bermeja’s non-verifiability as early as 1997, a year before formal negotiations on the Doughnut Hole boundaries reportedly commenced.

The inability to prove Bermeja’s existence demonstrably weakened Mexico’s negotiating position, as it could not use the island as a baseline for its territorial claims.

The perceived loss of territory and resources provoked strong reactions from Mexican politicians in subsequent years:

- In November 2008, six senators from the then-governing Partido Acción Nacional formally raised the issue in the Senate, citing “plentiful suspicions” that Bermeja might have been deliberately made to vanish before the treaty negotiations.

- PAN Deputy Jorge Nordhausen Gonzalez stated bluntly: “We are not certain whether there was an island involved or whether the area comprised a series of caves. That’s not important. What matters is that a portion of our territory was surrendered.”

- Former Mexican politician Elias Cardenas suggested that Bermeja’s disappearance might be attributable to rising sea levels caused by global warming, or, more provocatively, that the island “was disappeared by the CIA to capture the oil reserves as quickly as possible and confuse us with the border.”

The Definitive Search

When national pride and billions in oil are at stake, legends must be confirmed or laid to rest. The outcry over Bermeja’s absence triggered a series of increasingly sophisticated expeditions to find what history insisted should exist, or to prove it never had.

The 1997 Search

As negotiations with the United States approached, the Mexican Navy dispatched an expedition to locate Bermeja. Despite having modern navigation equipment and the historically documented coordinates, they found nothing but open water.

The 2009 UNAM Study

The most comprehensive investigation came in 2009, when the Mexican Congress commissioned UNAM for a definitive search. With a moratorium on oil drilling about to expire, the urgency was clear.

UNAM deployed sonar, aerial surveys, and geological analysis to investigate Bermeja’s supposed location. Their conclusion to Congress was unequivocal: the island does not exist and the seafloor shows no evidence it has for at least 5,300 years.

In 2009, the Mexican government officially removed Bermeja Island from its maritime charts.

Lingering Questions Among Researchers

Still, some researchers weren’t convinced. Arturo Carranza suggested the island may have existed elsewhere. Irasema Alcántara cited precise documents and photographs showing a landmass “unlike any island within a thousand miles.”

The scientific “non-finding” of Bermeja, despite advanced technology, did not entirely extinguish the mystery. For some, it shifted focus to questioning the completeness of the study or the possibility that Bermeja had existed elsewhere.

What Happened to Bermeja?

In the space between historical record and physical reality lies a fertile ground for theories. Some scientific, others verging on conspiracy.

The human mind resists unsolved mysteries, particularly when the answer might reveal uncomfortable truths about how we construct our understanding of the world. Several explanations have emerged to bridge the gap between Bermeja’s documented past and its absent present.

Theory 1: Natural Erosion or Submergence

The Claim: The island gradually eroded away or was submerged by rising sea levels over centuries.

The Problem: An island reportedly 80 square kilometres in size should have left significant traces. Shoals, a seamount, or seabed disturbance. The UNAM seafloor analysis found no such remnants.

Theory 2: Volcanic or Tectonic Activity

The Claim: Sudden geological events like earthquakes or volcanic activity caused the island to sink.

The Problem: The UNAM study found no geological evidence of a recently submerged island or a cataclysmic event. Geologists stated it would require a hydrogen bomb to make such a landmass completely vanish without a trace.

Theory 3: Cartographic Error

The Claim: Bermeja Island never physically existed at the coordinates 22° 33′ N, 91° 22′ W. Its presence on maps resulted from an initial mistake by early cartographers, faithfully but uncritically copied for centuries.

The Evidence: The modern searches found no island and no geological evidence suggesting an island had existed and disappeared. The UNAM study’s conclusion that no island had occupied the site for at least 5,300 years strongly supports this theory.

Errors in early cartography could stem from various factors: misinterpretation of navigational data (longitude was particularly difficult to determine accurately in the 16th century), a desire to fill in uncharted areas of maps, misidentification of temporary features, or simply copying from previously erroneous sources.

Most contemporary geographers and the UNAM study support this explanation. Jesús Israel Baxin Martínez described it as “simply a cartographic error replicated and unverified over more than 400 years.”

Theory 4: Deliberate Destruction

The Claim: Bermeja was deliberately destroyed by United States interests to gain a territorial advantage in the Gulf for oil exploration.

The Problem: This theory lacks credible evidence and faces significant logical challenges, including the logistical difficulty of covertly destroying an 80-square-kilometre island and the UNAM finding that no island existed at the site for millennia.

Theory 5: The “Trap Island” Hypothesis

The Claim: Bermeja might have been a “trap island”, a fictitious entry deliberately placed on a map by a cartographer to detect plagiarism by rivals.

Bermeja Among History’s Phantom Islands

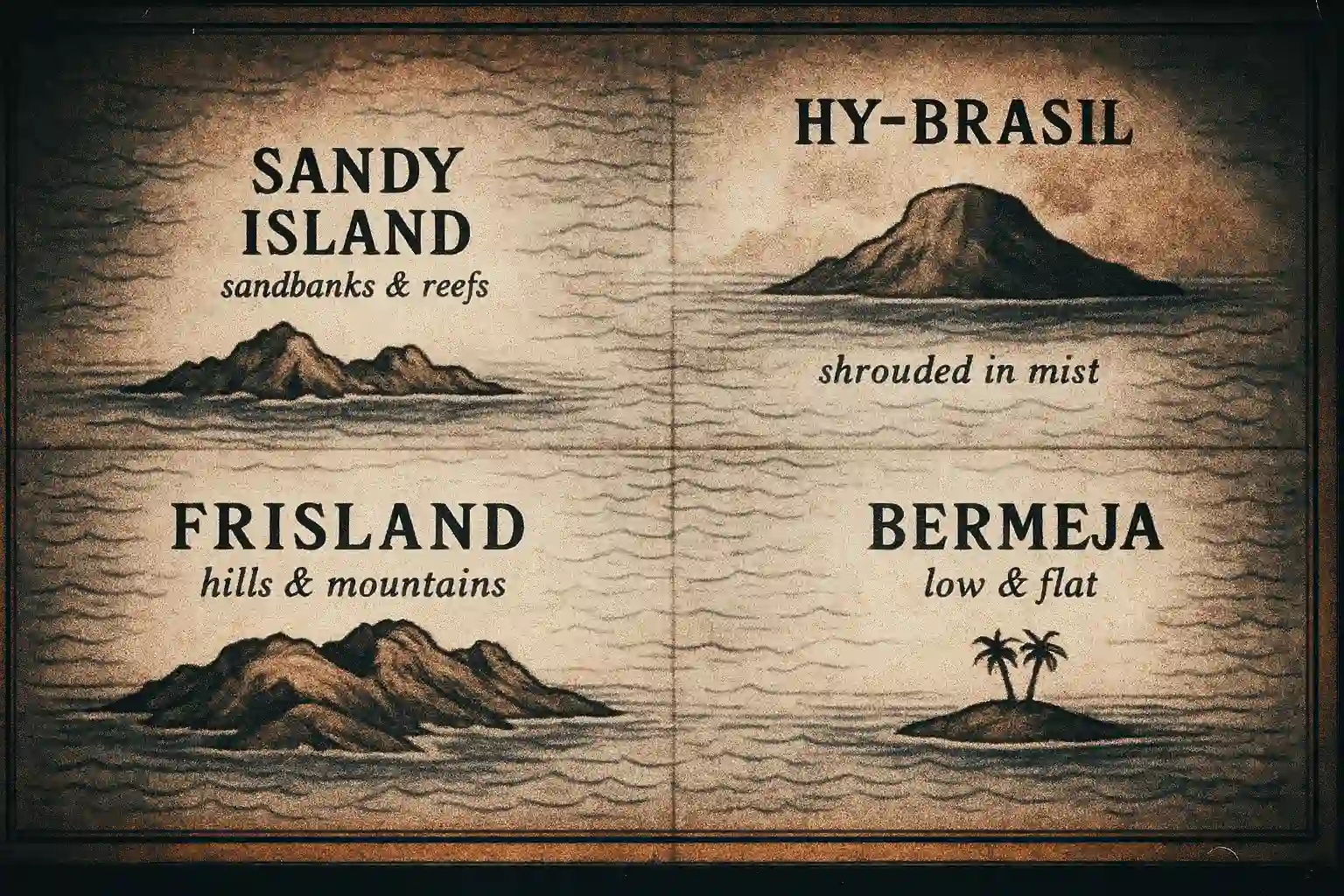

Bermeja is not a solitary ghost in the cartographic record. It belongs to a spectral family of places that never were. Throughout history, mapmakers have charted hundreds of “phantom islands”. The landmasses that appeared on maps, sometimes for centuries, before being exorcised by the cold light of exploration.

This curious subset of cartographic history reveals much about human psychology, the evolution of scientific knowledge, and how errors can calcify into “facts” through repetition.

Notable Phantom Islands

- Sandy Island (Pacific Ocean): Appeared on maps until 2012, when an Australian research vessel found only open ocean at its coordinates.

- Hy-Brasil: A legendary island west of Ireland, appearing on maps from 1325 onward, reportedly visible only once every seven years.

- Frisland: Appeared on North Atlantic maps throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, with explorers even claiming to have landed there.

Why Phantom Islands Appear and Disappear

Phantom islands typically originated from navigational errors, misidentification of natural phenomena, or deliberate fabrication. Once recorded by influential mapmakers, these non-existent features were often copied for generations without verification.

Their “disappearance” typically results from improved navigation technology, more rigorous surveys, and modern imaging capabilities.

What Makes Bermeja Different

Bermeja stands out due to the direct and substantial geopolitical consequences tied to its existence or non-existence. While many phantom islands are now merely historical curiosities, Bermeja’s status directly affected international boundaries and billion-dollar oil resource claims between two modern nations.

Bermeja in Mexican Consciousness

Maps don’t just represent physical space, they embody national identity, historical memory, and political aspiration. Within Mexico, the Bermeja narrative has escaped the dusty shelves of cartographic archives to become something far more powerful: a cultural touchstone that speaks to deeper anxieties about sovereignty, resources, and relationship with powerful neighbours.

A Symbol of Lost Sovereignty

For many Mexicans, Bermeja symbolises vulnerability to the loss of territory and natural resources, particularly in relation to the United States. Its “disappearance” taps into fears of exploitation and diminished national sovereignty.

The conspiracy theories surrounding Bermeja, especially those implicating the CIA in its destruction, are fuelled by historical distrust of the U.S. stemming from events such as the Mexican-American War and perceived interventionism throughout Mexican history.

Oil and National Identity

Given the critical role of oil in Mexico’s national budget and identity, the island’s connection to potentially massive untapped reserves makes its “loss” particularly poignant and politically charged.

As one geographer observed, the Bermeja case illustrates a cultural tendency where “people don’t care about what they’ve got, but they do care about what they’ve lost.” The island, largely ignored when presumed to exist, became a focal point of national concern once it was declared missing.

Media Coverage and Public Interest

The Bermeja enigma has captured significant media attention:

- BBC journalist David Cuen investigated the mystery (Mexico’s Missing Island)

- Mexican television network TV Azteca launched maritime research campaigns (Isla Bermeja – Wikipedia)

- Numerous online articles, videos, and speculative content continue to circulate (Mexico News Daily, Lonely Planet)

- Books like Edward Brooke-Hitching’s The Phantom Atlas feature Bermeja prominently (The Phantom Atlas on Amazon)

The public concern was significant enough to prompt the Mexican Chamber of Deputies not only to commission the expensive UNAM study but also to sponsor an exhibition of historical maps featuring Bermeja, demonstrating a desire to engage with this piece of national cartographic heritage.

The Unsettling Legacy

Some mysteries resist tidy resolution, instead unraveling into threads that lead to even deeper questions.

The saga of Bermeja Island isn’t merely about a missing landmass, it’s about the fragile foundations upon which we build our understanding of the world, and how easily supposedly fixed realities can shift beneath our feet.

The weight of evidence points overwhelmingly towards Bermeja being a phantom island, a cartographic error perpetuated through centuries of mapmaking tradition. Yet the specificity of its early descriptions by respected cartographers, its consistent reported size, and its persistent appearance on maps until the early 20th century make its “non-existence” more complex than a simple mistake.

Bermeja forces a confrontation with the nature of maps not as infallible representations of reality, but as historical artifacts subject to error, interpretation, and even manipulation. It underscores how perceived geographical “facts” can become deeply embedded in political strategy and national consciousness, exerting influence even from beyond the realm of physical existence.

The impact of this phantom was profoundly real. The island’s (non)existence became a pivotal factor in US-Mexico negotiations over oil-rich regions of the Gulf, with its absence arguably diminishing Mexico’s territorial claims and access to billions of barrels of oil. Something that never existed, or at least, could not be proven to exist, nevertheless shaped international borders and resource allocation.

The story of Bermeja is a testament to the constructed nature of “truth” when cartographic history, economic imperatives, political manoeuvring, and collective memory collide. It challenges our assumptions about the stability of geographical knowledge and the transparency of the processes that define national territories and allocate global resources.

The Question Remains

If Bermeja was a cartographic error, why did it endure for centuries in maps used to shape empires?

If it truly existed, what force erased it so completely?

And if something as substantial as an island can disappear, what else might already be gone?

Share your theory below, or continue exploring the lost, the hidden, and the contested in the Veriarch Case Files.

Comments (0)