In 1886–1887, an expedition at Akhmim in Upper Egypt pulled a parchment codex from a grave that was thought to be a monk’s. Inside was a ‘Gospel of Peter’ with a resurrection scene that no canonical gospel dares describe… towering figures, a talking cross, guards and elders looking on. Yet the same text appears to lift a crucial line about guarding the tomb straight from Matthew. A work that looks boldly original also reads, in places, like a copy. That contradiction is the hinge of this case.

A Monk’s Grave with No Field Notes

Start with what can be checked. The codex surfaced during the 1886–1887 season at Akhmim. Urbain Bouriant published the Greek texts in 1892 and said the book came from a grave ‘supposed to be a monk’s’. That wording matters. It is a cautious attribution, not a documented identity.

Egyptian archaeology in the 1880s was in transition. Scientific method was arriving, but much work still chased objects over context. Excavations were patchy, partage incentives pushed rapid recovery, and written records were thin. At Akhmim, the necropolis was worked by multiple parties and clandestine digging was common. No detailed field notebook survives for this specific find. There are no stratigraphic notes, no photographs of the burial, no plan drawings that would let a modern reader verify the ‘sealed tomb’ story that appears in later retellings.

The basic facts come with small but telling conflicts.

Some secondary listings put the discovery as ‘1886’, and a few older summaries give ‘1880’. The season log that ties it to 1886–1887 is the most specific and best supported. The spread itself is a warning. Later summaries repeat one another, and precision degrades as they do.

The codex did not hold a single text. Alongside the Gospel of Peter sat fragments of the Apocalypse of Peter and portions of the Book of Enoch. That mix matters because it hints at a collector’s taste or a community’s reading list, but without proper context, it cannot be read as a deliberate library. We know where the book ended up. We do not know how or why it was placed there.

Modern editors have also pushed back on the neater versions of the find story.

Scholars such as Tobias Nicklas and Thomas Kraus have noted that the popular claim of a fully ‘sealed’ and undisturbed monk’s tomb rests on retellings, not on a preserved, primary excavation record. Without that record, the discovery context remains a claim rather than a checkable fact.

Questions that follow from the record:

- Was the grave undisturbed before the French team arrived, or had it been opened earlier by dealers or locals drawn by the market in late antique textiles and books?

- Did the body hold the codex, or was the book beside the remains? Without photographs or a plan, we cannot say.

- If this was a monk’s burial, was there an inscription or a textile marker that justified the label? Nothing published records such a detail.

Those gaps are not decoration. They determine how much weight to put on the discovery story when we later try to read the manuscript’s meaning.

The Manuscript and the Missing Pieces

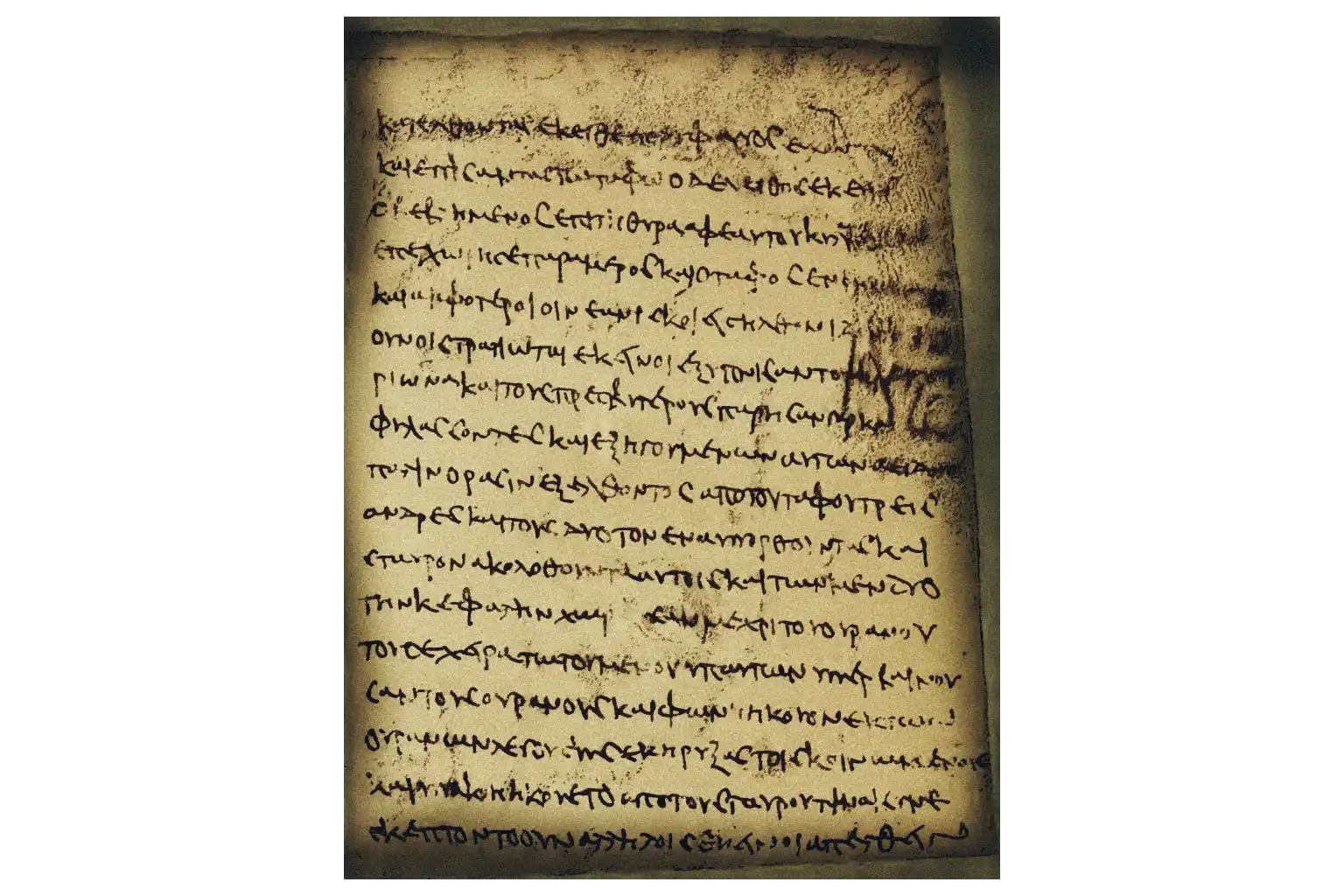

Separate the artefact from the text. The Akhmim Fragment is a parchment codex catalogued as P.Cair. 10759. Palaeography, the dating of handwriting by style, places the copying of this book somewhere between the 6th and the 12th century. Many entries and studies cluster around an 8th–9th century window, while some museum catalogues have floated earlier. That range is unusually wide. It reflects the difficulty of dating Byzantine-era Greek scripts without a securely dated comparator or clear archaeological context.

The contents we have are incomplete.

The Gospel of Peter in this codex begins mid-sentence and ends mid-sentence. Titles and ornamental marks show a scribe copied what was in front of him and no more. There is no sign he had the beginning or the end to hand. No other substantial manuscript has turned up to fill those gaps. Apart from two minor Greek fragments elsewhere, this codex is the main witness to the text.

The physical object is also hard to reach. The codex has been reported missing from its museum home. Scholars work from photographs and the 19th- and 20th-century publications. That is workable for reading the Greek, but it blocks fresh technical tests on the parchment, inks, sewing, and quire structure that could narrow the date or the place of copying.

A final point on time. The date most scholars give for the composition of the Gospel of Peter as a text is the mid to late 2nd century. If that is correct, the physical book in the grave is several centuries younger than the composition of the work it contains. That is not unusual. Late copies of early texts are the norm. It does, however, remind us that arguments about authorship and theology turn on the wording of a much earlier composition preserved in a later hand.

Key Terminology

- Codex: a bound book of folded sheets, the forerunner of the modern book, used in late antiquity in place of scrolls.

- Palaeography: the study of ancient writing. Scholars compare letter shapes and layout to dated samples to estimate when a manuscript was copied.

- Patristic evidence: writings by early Christian authors, often bishops or historians, used here as external testimony about which texts communities read and how they judged them.

- Passion narrative: the sequence of events from Jesus’ trial to his death and burial, sometimes extended to include the empty tomb and resurrection scenes.

Serapion’s Verdict – Condemned for Heresy

The earliest clear external reference to a ‘Gospel of Peter’ sits not in Egypt but in Syria.

Around 190–203 CE, Serapion, Bishop of Antioch, wrote to a church at Rhossus. He had allowed the congregation to read a gospel under Peter’s name, then withdrew that permission after seeing extracts. His judgment ran along two tracks. Most of the text aligned with accepted teaching, but some parts were ‘additions’ associated with the Docetae, a label used for Christians who said Christ only seemed to suffer.

We have Serapion’s words because Eusebius of Caesarea copied them into his 4th-century ‘Church History’.

‘For our part, brethren, we receive both Peter and the other apostles as Christ; but we reject intelligently the writings falsely attributed to them, knowing that such were not handed down to us’.

Serapion of Antioch, quoted in Eusebius’ Church History, c. 200 CEThat sentence explains why the title ‘Gospel of Peter’ later sits on lists of rejected books. It also sets the tone for how the fragment would be read once the Akhmim codex came to light. A title condemned in the 2nd century met a manuscript in the 19th.

Other early writers knew a ‘Gospel of Peter’ by title. Origen mentions it in passing in a different context centuries later. That reference talks about family traditions not present in our fragment, which suggests either that the title travelled across different works or that later authors sometimes mislabelled texts. It is a reminder that a title alone does not guarantee identity.

Two questions emerge. First, did Serapion and the Akhmim codex contain the same work? Second, even if they did, did Serapion correctly read its theology?

The rest of the case turns on those points.

Docetism Reconsidered – Was the Text Maligned?

Docetism comes from the Greek verb ‘dokeō’, meaning ‘to seem’. In simple terms, a docetist Christ does not truly suffer. Pain is only apparent. The Gospel of Peter fragment includes lines that look, at first glance, like evidence for that view. Two phrases are usually cited.

- Jesus is silent on the cross ‘as having no pain’. In a plain reading, that sounds like denial of suffering. A different reading is available. Early martyr accounts often praise believers for enduring pain with composure. Silence can be courage, not denial of flesh.

- Jesus cries, ‘My power, O power, you have forsaken me’ and is then ‘taken up’. Read as docetism, this maps to a divine ‘power’ abandoning a body and rising away. Others hear a poetic lament for strength failing and a compression of death and vindication into a single breath. In ancient narrative that is not unusual. Writers often telescope events for force.

Scholars who challenge the docetism charge argue that Serapion judged the text in a polemical moment. His role was to police boundaries. If a community at Rhossus used language that made some hearers uneasy, a bishop could move quickly to ban rather than to re-interpret. That does not mean he was wrong. It does mean we cannot treat his verdict as the last word.

What the fragment does strongly is shift blame for the crucifixion from Pilate to Herod and ‘the Jews’, while almost exonerating the Roman governor. That fits 2nd-century Christian apologetics that sought a less confrontational stance toward Rome. It also explains why a bishop would be wary. A text that softened Pilate’s role and stressed a cosmic, almost mythic victory would look suspect when orthodoxy was still being sketched.

The Docetism Debate: Two Readings of the Text

| Key Event | Phrase suggesting Docetism | Alternative Modern Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| On the cross | Jesus was silent ‘as having no pain’. | A portrayal of heroic endurance, common in martyr accounts. |

| Final words | The cry ‘My power, O power…’ followed by being ‘taken up’. | A lament over failing physical strength, not divine abandonment. |

Serapion's second-century verdict versus modern textual analysis of the key phrases.

A Tale of Two Gospels – Dependence on Matthew

The other flank of the debate is literary. Does the Gospel of Peter lean on the canonical gospels, or does it preserve an independent passion tradition?

The sharpest piece of evidence for dependence is a near-verbatim echo of Matthew 27:64, the elders warning Pilate about the risk that disciples will steal the body. The wording is so close that most scholars read it as direct literary borrowing from Matthew.

There is a refinement of that majority view.

Raymond E. Brown proposed that the dependence might not be on a written copy of Matthew, but on an oral version heard in readings at church. In that model, an author recreates familiar phrases from memory, which would explain why some lines are very close while others diverge.

A minority case argues in the opposite direction.

John Dominic Crossan’s ‘Cross Gospel’ theory posits that the Gospel of Peter contains a primitive passion source that predates even Mark. On this reading, the canonical evangelists shaped their accounts in light of a tradition that the Gospel of Peter preserves in part. The theory sets the unique features of the Akhmim fragment as ancient rather than late.

A practical test would help both sides. A full, quantitative comparison of Greek phrasing across the fragment and the canonical gospels, including function words and syntax, would sharpen the case for or against direct literary borrowing.

Until such a study is run on a wide enough sample, the present arguments rest on selected parallels and broad narrative shape.

Set the arguments side by side. The majority case must still account for the fragment’s striking scenes that lack canonical parallels.

The minority case must explain why the text also looks composite, with elements that mirror Matthew, Luke and John. Both positions explain some data and struggle with other data. That is why this case has not closed.

‘The passion narrative source embedded within the Gospel of Peter predates all other known passion accounts, including those in the canonical gospels’.

John Dominic Crossan, The Cross That Spoke (1988)Evidence of a Primitive Myth or a Late Legend?

The most arresting passage in the fragment is the only narrative in early Christian literature that tries to describe the moment of resurrection.

Guards are stationed at the tomb with a seal. The Jewish elders are there too. Two giant figures descend from heaven and go into the tomb. Three figures emerge, the two giants supporting a third whose head reaches above the heavens. Then a cross comes out behind them. A voice from above asks, ‘Have you preached to them that sleep?’ and a reply is heard from the cross: ‘Yes’.

There is no match for this in the canonical gospels. The closest parallels are general, not verbal. Mark breaks off at the empty tomb. Matthew gives guards and an earthquake, but no scene of Jesus striding out. Luke and John offer appearances after the event. The Akhmim fragment alone stages the act itself and assigns speech to the cross.

What does that imply?

Read one way, it looks like a primitive mythic telling that keeps the cosmic scale of early Christian proclamation and pushes it into a story. Read another way, it looks like a later, legendary flourish designed to magnify the event and settle doubts.

Both readings carry problems.

If early, why the echo of Matthew on the guard story? If late, why such bold departures elsewhere? Until new evidence narrows the dating, this scene will sit at the centre of the argument.

A note on genre. Ancient religious writing often shifts between historical narrative and visionary symbolism. A speaking cross is a symbol. The line is not a report of timber producing sound. It is a device that lets the author show that the proclamation has reached ‘those who sleep’, the dead. The question, for our purposes, is not whether the symbol is credible but whether its use points to an early or a late stage in the text’s life.

Resurrection Sequence: The Akhmim Fragment

Roman guards and Jewish elders are stationed at the sealed tomb.

Two giant figures descend from heaven and enter the tomb.

Three figures emerge: the two giants supporting a third, even larger figure whose head reaches above the heavens.

A cross follows the three figures out of the tomb.

A voice from heaven asks if the message has been preached to 'them that sleep'. The cross itself answers: 'Yes'.

Sources

Sources include: patristic writings from the second to fourth centuries, including Eusebius of Caesarea’s Church History which preserves the judgment of Serapion of Antioch, and later references by Origen; the primary manuscript evidence of the Akhmim Fragment itself (P.Cair. 10759), a medieval Greek codex containing the Gospel of Peter, the Apocalypse of Peter, and 1 Enoch; modern scholarly analysis from the late 19th century to the present, including foundational editions by H.B. Swete, theological reassessments by Raymond E. Brown, and the ‘Cross Gospel’ source theory proposed by John Dominic Crossan; and archaeological records relating to the discovery, including Urbain Bouriant’s 1892 publication of the find and modern analyses of 19th-century excavation practices in Egypt.

What we still do not know

- Grave context: whether the tomb was truly sealed, how the codex lay in relation to the body, and whether any inscription named the deceased.

- Manuscript date: the palaeographic range runs from the 6th to the 12th century. A narrower, methodical re-assessment would improve all downstream arguments.

- Textual scope: whether the original Gospel of Peter included infancy or ministry sections beyond the Passion. Our fragment cannot answer that.

- Identity with Serapion’s text: whether the Akhmim gospel is the same work condemned at Rhossus or another text that shared the title.

- Dependence pattern: a full, quantitative comparison of Greek phrasing across the fragment and the canonicals would sharpen the case for or against literary borrowing.

Comments (0)