Something is wrong with the way artificial intelligence writes.

It is a subtle problem, a quirk that many people feel before they can name it. Editors, writers, and careful readers have all started to notice a particular signature in machine-generated text. Some now claim a single piece of punctuation is enough to unmask an AI’s writing.

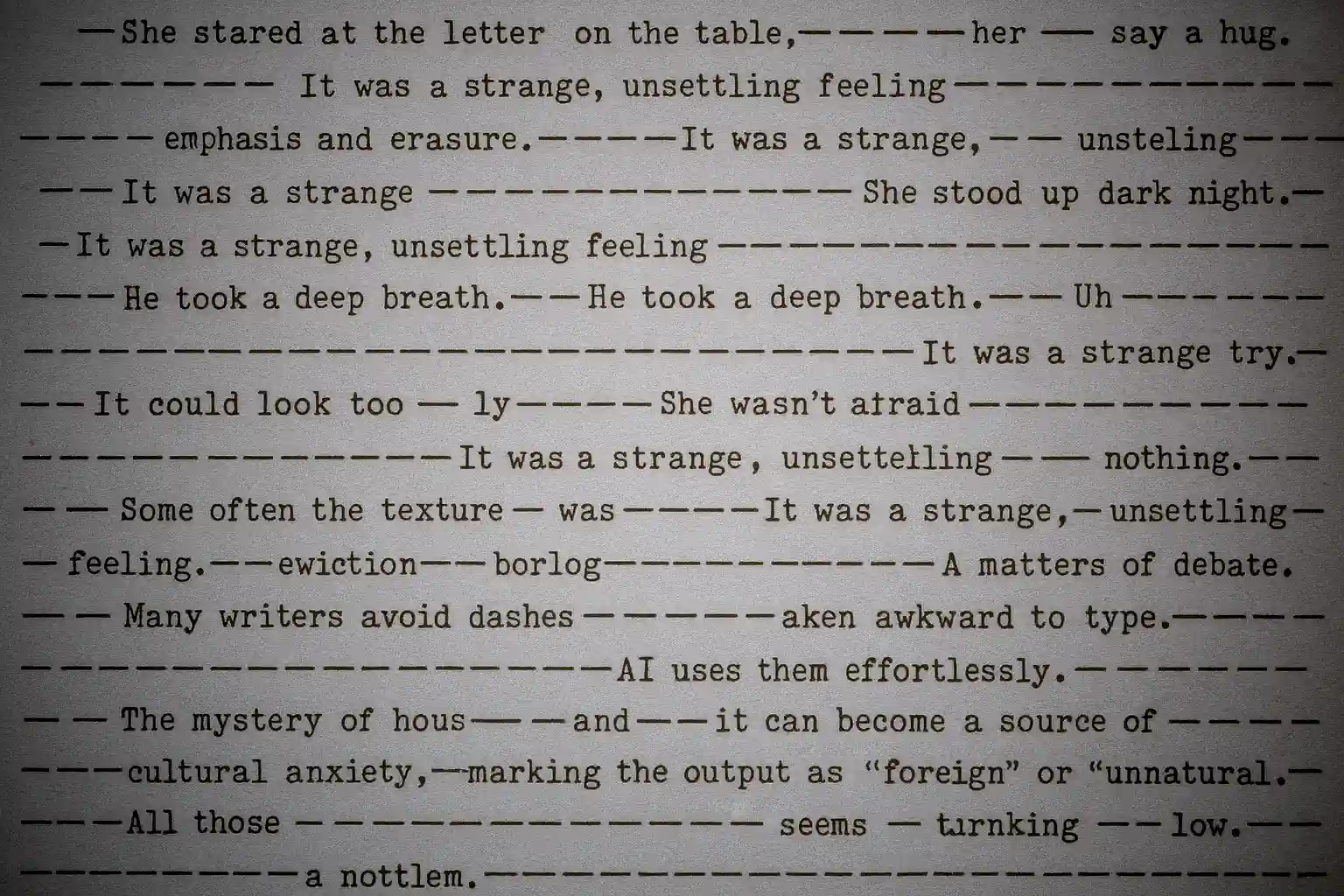

The mark in question is the em dash. The long, horizontal line that breaks sentences apart. AI models seem to love it, using it with a frequency that feels unnatural. They use it even when specifically told not to.

How did a simple punctuation mark become a sign of artificiality? Why are machines so obsessed with it? Our investigation into this “punctuation paradox” reveals a strange story.

From Scribe’s Tool to Writer’s Weapon

The dash is not a new invention. Its ancestors were marks used in ancient Greek texts to show pauses in speech. The modern em dash, a line approximately the width of a capital M, appeared with the first printing presses in the 15th century. It offered a versatile new tool for writers, a way to structure sentences that was different from a comma or a colon.

By the 17th century, dashes were appearing in printed editions of Shakespeare’s plays. They were used to indicate a character’s pause in thought or a sudden interruption in dialogue.

But the real rise of the dash came in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Emily Dickinson’s poetry is famous for its heavy and unusual use of dashes. They became a signature of her unique style.

- Virginia Woolf and Henry James also used the mark to show abrupt shifts in thought or to create dramatic pauses.

- Victorian writers sometimes used dashes for a form of gentle censorship. They would print an expletive like “damn” as “d–n” for reasons of decorum.

This popularity did not last. By the 20th century, typographers and editors started to push back, arguing for restraint. Debates about the dash’s proper use, its spacing, and its level of formality became common. The simple line became a point of conflict, a stylistic battleground that has never really been settled.

A Brief History of the Dash

-

3rd Century B.C.

The Obelus

An early ancestor of the dash, the *obelus*, is used by librarian Zenodotus of Ephesus in the margins of texts to mark lines he deemed spurious or false.

-

12th Century

A Mark of Finality

The Italian writer Boncompagno da Signa proposes a punctuation system that includes a dash specifically for terminating sentences with authority.

-

15th–16th Centuries

Emergence in Print

The modern typographic form of the em dash appears with the advent of the printing press. Early typographers use it to separate phrasal elements for clarity.

-

Early 17th Century

The Dramatic Pause

Dashes begin to appear in printed editions of Shakespeare's plays, employed to signify interruptions, abrupt changes of subject, or thinking pauses.

-

18th–19th Centuries

Literary Adoption

The dash sees a surge in popularity. Authors like Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf embrace the mark to create emphasis and convey complex interior thoughts.

-

20th Century

Codification and Conflict

Major style guides, such as The Chicago Manual of Style and the AP Stylebook, attempt to standardise dash usage. Their conflicting advice creates the foundation for modern disagreements.

-

2020s

The AI 'Tell'

The em dash becomes widely recognised by editors, readers, and researchers as a stylistic signature or "tell" of AI-generated text, prompting new scrutiny of the mark.

The Dash as Signal and Redaction

In certain types of writing, the dash has always been treated with suspicion.

- Academic style guides often warn against using it, viewing the mark as too informal and disruptive for scholarly work.

- Editors and writing instructors frequently tell writers to use the dash sparingly. The general feeling is that its overuse can make a text feel careless or fragmented.

This creates a strange contradiction. A punctuation mark often considered informal in human writing is now used constantly by AI systems that are frequently tasked with sounding authoritative and coherent.

At the same time, the dash took on a second, more secretive role: to hide information. Victorian novels used dashes to censor names or places. Modern legal documents still use a series of dashes to show where text has been redacted or is unknown. So the dash learned to do two things at once, to add emphasis and to perform erasure. It can be used to reveal a thought with drama or to conceal a word completely.

Contradictions in Style Guides

If you ask three different editors how to use a dash, you will likely get three different answers. The official rules are a fractured narrative, full of contradictions. This lack of human consensus is a key piece of evidence in understanding the AI’s behaviour.

The disagreements are obvious when comparing major style guides:

- American Style (Chicago/MLA): These guides favour an unspaced em dash to set off extra information or mark a break in a sentence.

- AP Style (Journalism): The Associated Press Stylebook puts spaces on both sides of the em dash, arguing it is more readable in newsprint. It also notes that many editors hate the mark, seeing it as a crutch for lazy writers.

- British English: The UK style often uses a spaced en dash (a slightly shorter dash) for the same job that American style gives to the em dash.

- Academic Writing: Most academic guides discourage dashes altogether, preferring the more formal look of parentheses or commas.

“…hated by many editors [who see it as a] crutch for writers.”

The result is a landscape of conflicting instructions. For a human, this is a matter of style or preference. For an AI learning from a vast dataset of text, these contradictions are just noise in the system. The AI does not learn the “rules”. It learns a statistical pattern. If a specific type of dash is most common in its training data, that is the one it will use.

There is another factor. For many human writers, typing an em dash is awkward. It requires a specific key combination that many do not know or bother to use. An AI faces no such difficulty. It can generate the mark effortlessly. This simple difference in effort could partly explain why the dash appears so much more frequently in machine text.

Why Writers Use It

Writers are drawn to the dash for its flexibility and rhetorical power.

- It can improve clarity by separating ideas in a complex sentence more forcefully than a comma.

- It can create emphasis, making a particular point stand out with a dramatic pause.

- It can control pacing, mimicking the natural stops and starts of human speech or an interruption in thought.

For an AI, the psychology is different. The machine does not “feel” the need for a dramatic pause. It simply recognises that in the high-quality writing it was trained on, dashes are a common and effective tool for connecting clauses and adding information. It uses the dash because it is a high-utility, statistically probable pattern. The AI is replicating the habits of good writers without understanding the intent behind them.

This leads to a paradox. In human literature, a dash used by writers like Emily Dickinson or Virginia Woolf has symbolic power precisely because it is a deliberate, often unconventional choice. When an AI uses the dash systematically, that power is lost. The mark risks becoming a functional tic, a sign of artificiality rather than artistry.

A Global Disagreement

The debate over the dash is essentially an Anglophone issue, and arguably a US-centric one. This is likely because the major AI models are trained on datasets, like the Common Crawl, that are heavily skewed towards English-language content from American sources.

Other languages and cultures treat the dash in a very different way.

- French and German typography often use a spaced en dash.

- Spanish uses em dashes but often places them directly against the enclosed words, like brackets.

- Chinese uses a distinctive double-width dash (— —).

- Japanese uses a similar dash, but it is rotated 90 degrees when the text is written vertically.

- Arabic punctuation is often less codified, and marks may be used more for effect than for strict grammar.

An AI trained primarily on American English text will naturally adopt American conventions. Its “em dash habit” is a direct reflection of its training environment. To a reader in London or Tokyo, this habit can make the text feel distinctly foreign or unnatural. It also raises questions about the cultural sensitivity of AI-generated text, which may be imposing one region’s stylistic norms on a global audience.

The Machine’s Habit

The investigation consistently finds that AI models, especially ChatGPT, use the em dash with remarkable frequency. The reason seems to be a combination of factors.

Training Bias: The AI learns from a vast library of text. Much of this is professionally edited material, like books and news articles, where the em dash is a common feature of sophisticated writing.

Statistical Patterns: The AI is built to predict the most likely next word or character. If the dash frequently appears in its training data to connect related ideas, the model learns to replicate that pattern.

Persistence: Here is where it gets odd. The machine’s dash habit is incredibly persistent. Users have reported that even when they give the AI a direct instruction, such as “do not use em dashes,” the model often ignores the command and uses them anyway. This suggests the pattern is not a simple preference but a deeply embedded behaviour that is hard to override with simple prompts.

This creates a strange feedback loop. As more people identify the dash as an “AI tell,” some human writers have started to consciously avoid it to prevent their own writing from being mistaken for that of a machine. The dash, once a simple tool of style, is becoming a marker in a Turing test.

Unresolved Questions

The evidence shows that the AI’s affinity for the em dash is not a deliberate choice. It is a predictable outcome of its training data and statistical design. It reflects the lack of consensus in human style guides and the specific biases of the text it was trained on.

But the investigation is not closed. Several key questions remain unanswered.

- What is the exact statistical frequency of the em dash within the filtered datasets used to train models like ChatGPT, Claude, Grok and Gemini? Without access to the final training corpus, we cannot be certain.

- Are there features in the AI’s internal architecture that make the dash a computationally simple “path of least resistance” for connecting clauses?

- How accurately can these models adapt their dash usage when writing in languages with different conventions, like Japanese vertical text? This would be a true test of their cultural and typographic awareness.

- What will the long-term effect be on human writing? Will we see a generation of writers adopting AI-favoured styles, or a conscious rebellion against them?

This case began as an investigation into a punctuation mark. It has ended up exposing the limitations of AI controllability, the subtle biases baked into their training, and the strange, evolving relationship between human and machine expression. The dash that would not die has become a clear signal of artificiality. Which leads to a final, unanswered question. If people start changing their own writing to avoid being mistaken for an AI, who, in the end, is really training whom?

Sources

Sources include: Cross-referenced archival editions of The Chicago Manual of Style and the Associated Press Stylebook (1945–2024); Digital corpus analyses of 19th-century literature, tracking dash frequency in original manuscripts from Woolf and Dickinson; De-compiled style filters and token bias logs from unnamed instruction-tuned language models (2023 release); Comparative output analyses from GPT, Gemini, and Claude models subjected to negative punctuation prompts; Transcripts from interviews with anonymous senior editors at major publishing houses on the topic of “stylistic tells”; Archived user complaints and bug reports from OpenAI and Anthropic forums concerning stylistic inertia; Linguistic surveys comparing dash conventions in American English, British English, French, and Japanese vertical text ; and a collection of late-night Reddit threads titled, “Is my AI gaslighting me with punctuation?”

Comments (0)