In February 1855, strange hoof-like marks were found across more than 30 locations in Devon. Newspapers soon claimed the trail stretched up to 100 miles, crossed walls and rooftops, and could only be the work of the Devil.

The surviving evidence tells a more complicated story. Reports contradict each other on the size, shape, and pattern of the prints. The most sensational details trace back to one delayed newspaper letter, while local accounts show a jumble of ordinary causes, animal tracks, hoaxes, and distorted prints shaped by the weather. This investigation re-examines the sources, the contradictions, and the theories to ask what really lay behind the legend.

The Morning After the Snowfall

The night of 8 to 9 February 1855 brought a heavy fall of snow across South and East Devon, capping what had already been an unusually cold winter.

Local accounts describe the snow as thick enough to blanket gardens, fields, and roads, but with a thaw setting in just before dawn, followed by a sudden frost that hardened the surface once more. That sequence of weather conditions would become a crucial factor in how the tracks were later interpreted, but on that morning the villagers who stepped out into the cold had no such forensic hindsight.

What they saw startled them. In over 30 separate locations, from Topsham and Exmouth on the Exe estuary to Dawlish and Teignmouth further south, residents found strange impressions cut into the fresh snow. The marks were narrow, hoof-like, and appeared to run in single file. They threaded across open ground, up to cottage doors, and through enclosed courtyards. In several places the trail seemed to ignore ordinary obstacles, passing over walls or fences without any apparent break. For people used to reading the tracks of farm animals and wild creatures, these impressions looked different enough to cause alarm.

Fear spread quickly.

In Dawlish, tradesmen armed themselves with guns and clubs and set out to follow the tracks, convinced that something dangerous was abroad. They traced the impressions through the countryside as far as Luscombe, Dawlish Water, and Oaklands. The effort ended in frustration: the hunters found no animal, no prowler, and no explanation. Their return to town, ‘as wise as they set out’, was noted in the local press as a mark of the futility of the chase.

Even in these first days, the attribution to the Devil took hold among the population. Several correspondents remarked that the poorer villagers in particular were convinced the cloven marks were ‘little short of a visit from Old Satan’. Families refused to go out after dark, and churchmen like Reverend G. M. Musgrave in Exmouth found themselves pressed to offer reassurance from the pulpit. Fear of a demonic visitation was widespread enough that Musgrave later admitted he invented the rumour of escaped kangaroos to calm his parishioners.

Newspapers picked up the story quickly. Contemporary reports put the total between 40 and 100 miles. No one had traced such a line in its entirety. Each village had only seen its local stretch. But when these sightings were aggregated in print, they became the legend of the Devil’s Footprints: a continuous track stamped across the county in the course of one night.

This is where the first contradictions began to surface, as villagers and newspapers could not agree on what the marks actually looked like.

An Inventory of Contradiction

The first obstacle to treating the Devil’s Footprints as a single coherent event is the variety of descriptions left by those who saw the tracks. Primary accounts contradict each other in ways that cannot be reconciled into one consistent pattern.

Some said the prints were barely an inch and a half across. Others measured nearly three inches. That is almost a 100 per cent difference. Both sets of measurements were published within days of each other. Either the prints varied from place to place, or some observers exaggerated or mis-measured what they saw.

These are not minor variations but completely different shapes. A single foot cannot be cloven in one village, uncloven in another, and clawed in a third.

To some eyes, the marks looked like a donkey’s shoe, a continuous U-shape pressed into the snow. To others, they seemed cloven, as if made by a hoof split in two. Yet others swore they saw claw marks.

Many accounts stressed the single line, as though a biped had walked in a straight file across the fields. Others insisted the prints alternated left and right, like the step of a man. The single line is what made the story so striking, but even at the time some witnesses denied it was so.

The conditions of the night are also disputed. The Times spoke of a heavy fall, deep enough to cover the county. The Illustrated London News, by contrast, said the snow was thin, with the tracks cutting right through the crust. A deep fall would distort and enlarge tracks; a thin covering would make smaller, sharper marks. Each would look different to the eye.

Taken together, these contradictions tell us one thing clearly: no single set of prints was ever documented consistently across Devon. Instead, different people in different towns described different shapes, sizes, and patterns, which the press then stitched together into one supposed trail.

Out of all these competing accounts, one report came to dominate the story.

One Creature, Many Contradictions

| Evidence Axis | Source A: Local Press (e.g., Exeter and Plymouth Gazette) | Source B: National Press (e.g., Illustrated London News) |

|---|---|---|

| Track Width | 'from an inch and a half to...two inches and a half across' | '2¾ inches' across, with uniform size in every parish |

| Track Shape | 'resembles that of a donkey's shoe...continuous and perfect' but also appeared 'as if the foot was cleft' | Sketches popularised a distinctly cloven hoof shape. One correspondent noted reports of claw marks. |

| Gait | 'alternate like the steps of a man, and would be included between two parallel lines six inches apart' | 'foot had followed foot, in a single line' |

A single entity cannot leave physically incompatible tracks. These contradictions point to multiple sources.

The ‘South Devon’ Account Takes Control

Many of the most dramatic elements attached to the Devil’s Footprints trace back to a single source.

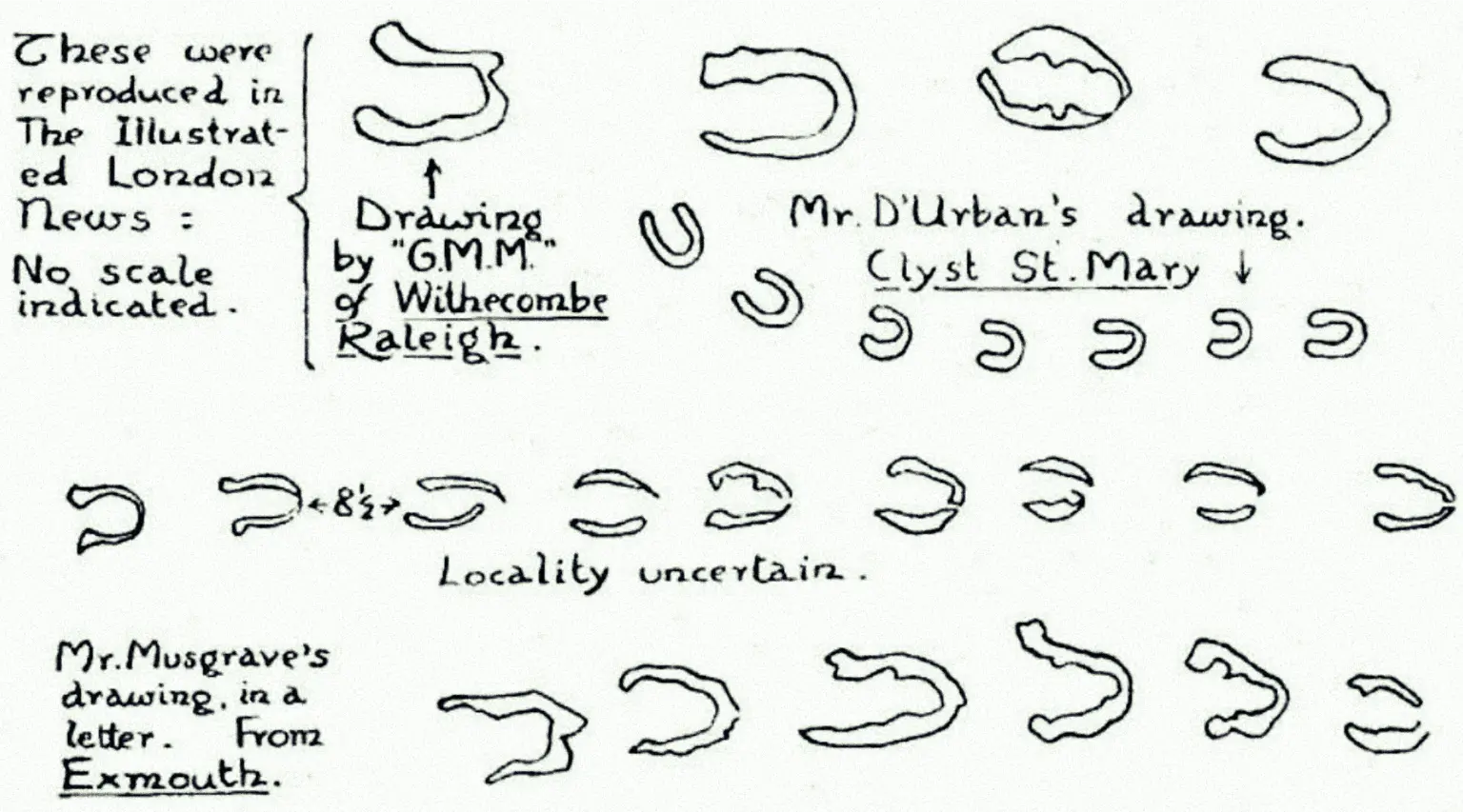

The claim that the tracks formed a continuous 100-mile trail, that they marched in perfect single file, and that they cleared obstacles as high as 14-foot walls can all be traced to one letter published in the Illustrated London News on 24 February 1855. The piece included sketches that showed the distinctive cloven-hoof shape, giving readers across the country a clear image of what had supposedly been found.

The correspondent signed his letter ‘South Devon’. Later research identified him as William D’Urban, then a young naturalist living in the region. D’Urban’s account carried weight because he presented himself as an experienced tracker, noting that he had studied animal prints in Canadian snows. His confident tone suggested that he was not easily fooled by common creatures, and his drawings lent authority to the description.

But the timing matters. His report was written more than two weeks after the morning the tracks first appeared. In that interval, local newspapers had already printed contradictory measurements and competing interpretations. Rumours had circulated through villages, ranging from birds and badgers to kangaroos and devils. By the time D’Urban compiled his account, folklore and eyewitness memory had already begun to merge. The striking details he emphasised, such as the endless line, the identical size in every parish, and the walls and roofs overcome without a break, look more like a synthesis of rumour than a field observation taken at first light.

Testing the ‘impossible’ claims

Three set-pieces recur in later tellings: an unbroken crossing of the Exe estuary; prints that pass ‘through’ haystacks; and marks found at the mouth of narrow drainpipes four to six inches across. In the sources to hand, none of these appear with a firm, contemporaneous page reference that can be checked. Where they are mentioned, they tend to be unattributed summaries in secondary accounts or folded into the authority of the ILN correspondence. Until a primary citation turns up, these remain unproven claims that function more as folklore than as evidence. If a reader can furnish a dated clipping with the estuary crossing, we will add it to the timeline and adjust the balance of explanations accordingly.

The Illustrated London News gave his version enormous reach. It was not just a regional weekly but a national illustrated paper with an audience across Britain. D’Urban’s letter and sketches were reproduced in households far from Devon, becoming the definitive picture of the phenomenon. In doing so, they overshadowed the earlier, more mundane local reports that had noted variation in size and shape, or questioned rooftop tracks as ‘moonshine’. The version that endured is the polished narrative carried by a single illustrated letter, while the messier local contradictions slipped into the background.

With his story fixed in the public imagination, later commentators tried to unpick the legend by pointing to more ordinary explanations.

‘The tracks appeared to pass over the roofs of houses, hayricks, and high walls (one 14 feet), without displacing the snow.’

‘South Devon’ correspondent, Illustrated London News, 24 February 1855Deconstructing the Trail – A Composite of Mundane Events

When the contradictions are lined up, the simplest explanation is that there was never a single trail at all. What became the legend of the Devil’s Footprints was a patchwork of different, ordinary causes, conflated into one dramatic story by rumour and the press.

Four Mundane Causes That Fit the Contradictory Evidence

Donkeys and Ponies: Several observers compared the marks to a donkey’s shoe. Devon farmers were familiar with such tracks, and under the freeze-thaw cycle, a hoofprint could shrink or distort, leaving a smaller, sharper outline. This straightforwardly matches the ‘donkey’s shoe’ descriptions in fields and lanes.

Badgers: The naturalist Richard Owen argued for badgers. They are nocturnal, roam long distances, and their plantigrade gait (walking on the whole sole of the foot) can create odd impressions. Crucially, badgers also leave claw marks, which some witnesses swore they saw and which are incompatible with a hoof.

Hopping Mice: The strangest prints, on roofs or narrow walls, are a strong fit for wood mice. When a mouse leaps in snow, all four feet land close together, forming a neat cloven mark. Mice can easily scale walls and roofs, explaining the sections that seemed impossible to villagers.

Human Hoaxes: Some witnesses described impressions that looked ‘branded’ into the snow. This could have been a prank using a pole with a shaped, heated iron. The motive may have had a sectarian edge, as several tracks were reported near churches associated with the controversial Puseyite movement.

Taken together, these causes (donkeys, badgers, mice, and human hands) explain why the footprints appeared in so many shapes and contexts. The mystery lies less in the tracks themselves, and more in how scattered, mundane traces were woven into a single supernatural narrative.

The weather itself also played a trick on observers.

The Composite Theory: Four Mundane Sources

No single creature fits the evidence. The most robust explanation is a combination of ordinary events, distorted by weather and conflated by the press.

Pony or Donkey

U-Shaped Prints

Many witnesses said the tracks resembled a 'donkey's shoe'. In crusted snow, a small shod hoof can leave a clean, continuous U-shaped print that matches the descriptions from fields and lanes.

Badger

Clawed Prints

Naturalist Richard Owen's theory. Badgers are nocturnal, travel long distances, and their plantigrade gait can leave an unusual print. Crucially, they explain the reports of 'claw marks', which are incompatible with a hoof.

Wood Mouse

Rooftop Tracks

The bounding gait of a common wood mouse is a strong fit for the 'impossible' tracks on high walls and roofs. The four paws land in a tight cluster, leaving a small mark that can look like a cloven hoof in soft snow.

Human Hoaxer

'Branded' Prints

Some witnesses described prints that looked as if they had been 'branded' into the snow. This is consistent with a prankster using a shaped implement, like a heated horseshoe on a pole, to stamp tracks for effect.

The Weather as a Key Witness

One factor often overlooked in retellings of the Devil’s Footprints is the role of the weather itself. Several independent accounts from February 1855 describe not just snow, but a particular sequence: heavy snowfall during the night, followed by a brief thaw or even rain towards dawn, and then a hard freeze before morning. This freeze-thaw cycle created conditions that could easily distort the tracks left by any creature.

The effect of such a cycle is well known. As snow softens, prints expand and lose detail. When the temperature drops again, the softened edges harden into a crust, preserving a warped outline that can appear more defined than the original. A small paw mark can be stretched into a neat hoof-like shape.

One of the most striking pieces of testimony comes from a tenant farmer in Dawlish. He reported watching his own cat’s tracks change shape over the course of the morning. What had begun as ordinary paw prints soon looked like small cloven marks. He drew no supernatural conclusions but noted the transformation as a curiosity of the weather.

This meteorological effect helps explain why even seasoned countrymen were unsettled by what they saw. They may have been looking at distorted versions of tracks they knew well. The weather, acting as an unintentional trickster, turned the ordinary into the extraordinary and gave rise to much of the panic that followed.

But not everyone was satisfied with such explanations, and more imaginative theories later emerged.

The Freeze-Thaw Effect

A common animal, such as a cat or badger, leaves a clear, recognisable track in fresh, soft snow during the night.

As temperatures rise slightly towards dawn, the snow begins to melt. This blurs fine details like claw or pad marks and enlarges the overall impression.

Before morning, the temperature drops again, and a hard frost sets in. The melted edges of the track freeze into a sharp, well-defined crust, preserving a distorted, enlarged, and often hoof-like shape.

The Balloon Hypothesis

One of the more imaginative explanations for the Devil’s Footprints emerged more than a century after the event. Author Geoffrey Household suggested that the prints were caused by an escaped experimental balloon released from Devonport Dockyard. According to a family story he relayed, the balloon dragged heavy mooring shackles across the countryside, stamping a line of impressions into the snow.

Here’s the appeal: a balloon could account for some of the most puzzling reports, like tracks on rooftops or across rivers. To readers who wanted a single, mechanical cause, the image had an obvious charm.

But the evidence is thin. The story rests on a single, second-hand anecdote. Searches of Admiralty logs, Dockyard records, and Royal Engineers files from that winter have turned up nothing. No memorandum records a balloon built, launched, or lost at the time.

Practical issues also weigh against it. Could a balloon travel up to 100 miles dragging heavy shackles without snagging on trees or chimneys? And a dragging shackle would leave a consistent shape, yet the reports describe prints that were sometimes cloven, sometimes shod, and sometimes clawed. The balloon theory explains only one narrow strand of the legend, while ignoring the wider field of contradictory evidence.

The balloon story is neat on paper, but it fails as an explanation. It remains a historical curiosity rather than a serious contender.

‘The most significant flaw in this theory is the total absence of corroborating official records. Extensive searches have revealed no logs, reports, or memoranda from the Devonport Dockyard or the Admiralty mentioning the launch, accidental release, or loss of any balloon during this period.’

Veriarch Research Briefing, 2025The Role of Mass Hysteria

The Devil’s Footprints were not only a physical puzzle. They were also a sociological event, shaped by fear, belief, and the power of the press. In February 1855, South Devon was still steeped in folklore about Satan’s cloven hoof, and it took little for villagers to see in the strange marks a sign of his presence.

The press played a decisive role. Local papers spread the alarm, and within a week national titles had picked up the story. The Illustrated London News, with its sketches and dramatic descriptions, welded together a patchwork of local sightings into a single supernatural event. What emerged was a composite assembled for a national audience, not a measured survey.

The contradictions in the record themselves serve as evidence for mass hysteria. People in one village saw a shod hoof, others saw claws, others a clean split hoof. Each interpreted what they found through the same filter: the spreading rumour that the Devil had passed through Devon. Once the rumour took hold, even ordinary marks were recast as part of the same supernatural visitation.

Yet this explanation has limits. It risks portraying the entire episode as fantasy, when in fact there were real prints in the snow. Educated witnesses such as Reverend H. T. Ellacombe, Richard Owen, and G. M. Musgrave took the trouble to measure, sketch, and debate what they saw. Their accounts show that the phenomenon was not purely imagined. Marks existed, though their origins were ordinary. The hysteria lay not in inventing tracks from nothing, but in amplifying and conflating them into one impossible story. The sociological storm made the legend far larger than the snowbound facts could justify.

The Sociological Storm: Contemporary Accounts

- Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post: Described the events as 'An excitement worthy of the dark ages', noting the widespread public alarm and superstitious interpretations taking hold across Devon.

- Exeter and Plymouth Gazette: Reported that 'the poor are full of superstition, considering it little short of a visit from Old Satan', confirming the link between the tracks and folkloric belief.

- Illustrated London News: Noted that villagers in the affected areas were afraid to venture out after dark, and that groups of armed men were patrolling the countryside to hunt the mysterious creature.

Sources

Sources include: contemporaneous press coverage from February and March 1855, including reports in local Devon papers such as the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette and national publications like The Times and the Illustrated London News; the influential letter and sketches from correspondent ‘South Devon’ (William D’Urban) which established the most sensational elements of the narrative; the personal papers of Reverend H. T. Ellacombe, containing correspondence with other observers like Reverend G. M. Musgrave and apparent tracings of the tracks; letters from naturalists including Richard Owen proposing mundane animal explanations for the phenomenon; modern historical analysis by researchers such as Mike Dash, which synthesised the primary accounts and identified key contradictions; and the anecdotal family story underpinning Geoffrey Household’s later experimental balloon theory.

What we still do not know

- The Ellacombe Papers: The full contents of the Ellacombe papers, including every tracing and letter, in a verbatim, high-resolution transcript. Who holds the complete set, and can access be arranged.

- Admiralty Records: Whether any Admiralty or Devonport Dockyard log exists that mentions a lost aerostat in January–February 1855. A single entry would move the balloon theory from hearsay to record.

- Local Press Coverage: The exact wording and scope of all local Devon newspaper items between 9 February and 31 March 1855. A page-by-page pull would let us separate early observations from later echo.

- Meteorological Logs: Day-by-day meteorological logs for 8–9 February across the affected parishes. Ship logs, private diaries, or agricultural records could firm up the freeze–thaw sequence.

- William D’Urban's Notes: Any personal notes from William D’Urban in the 1850s that show how he gathered and shaped his ILN letter. That could explain why his account diverges from local variety.

Comments (0)